—continued from page 1

the resort workers in what is only the second round of negotiations. The bad treatment by management goes back to the beginning—December 1998—when the hotel’s new owners, the KSL Recreation Group, bought the hotel for half of its construction cost after the banks foreclosed on Japanese developer Takeshi Sekiguchi.

No way to treat workers

The workers, many of whom had been with the hotel since it opened as the Grand Hyatt Resort and Spa in 1991, were told they would have no jobs and had to stand in line with everyone else and reapply as a new hire. The ILWU said this was no way to treat a loyal and skilled workforce. It was the workers who made the hotel a first-class resort and the workers should keep their jobs.

At first KSL ignored the union’s request “to keep the workers working,” so the ILWU took the message to the Maui community in radio and newspaper advertisements and to institutional investors who had millions of dollars invested with KSL’s parent company KKR (Kohlberg, Kravis, & Roberts). The ILWU also used its political influence with Mayor Kimo Apana and the Maui County Council which passed a resolution in support of the workers.

KSL got the message and on December 24, 1998, the day before Christmas, KSL western division president Scott Dalecio agreed to give preference to current employees and to negotiate a new contract with the ILWU.

Second-class wages

It took 19 months to reach a fair settlement on that first contract. KSL wanted a first-class resort and first-class workers but only wanted to pay second-class wages and benefits. The company demanded a series of reductions in benefits and other contract terms which were lower than what every other Maui hotel was giving their workers

The Grand Wailea membership refused to give in and held rallies and other actions to take the message to the Maui community. The ILWU continued to keep KKR investors informed and sent faxes and e-mail to thousands of travel agents and travel wholesalers about the ongoing contract dispute with management. It took 19 months but a settlement was finally reached and ratified by members in July 2000. The contract would run for a little over three years and expire on October 31, 2003.

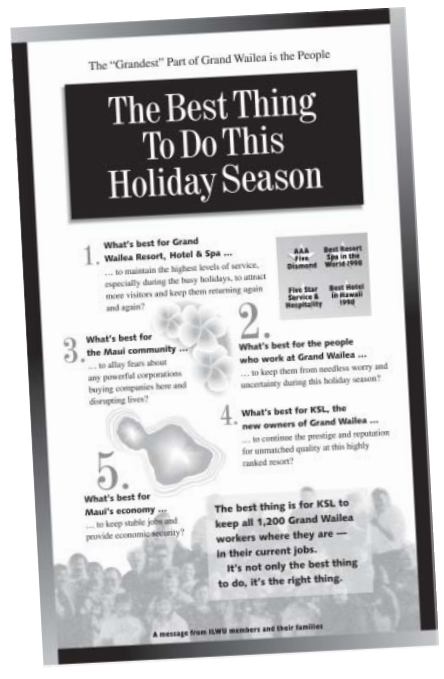

This ad ran in the Maui News in December 1998.

Over the three years, management’s attitude and behavior remained the same. Workers continually complained of unfair treatment by management. The union constantly filed grievances, which end in impasse or remain unsettled.

These are the reasons the second round of negotiations promise to be just as difficult and contentious as the first round.

Are the workers at fault?

An outside observer might wonder if maybe Grand Wailea workers might share part of the blame for the hostile and bad relationship between management and employees. Let’s answer this question by taking a closer look at KSL.

KSL was founded in 1993 by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Company (KKR), a multi-billion dollar investment firm that specializes in buying other companies, reorganizing or restructuring that company, and making a profit for itself and its investors in the process. Since 1976, KKR was involved in 110 management buyouts involving a total of $114 billion of total financing (see their website at www.kkr.com).

KKR uses other people’s money, particularly public employee pension funds, to finance their takeover efforts. Once in control, KKR restructures the companies to maximize wealth for the new investor/owners of the company. This is usually done at the expense of the existing management and employees of these companies—operations are merged, shut down or sold off; jobs are cut; wages and benefits trimmed. The idea is to trim the fat and make a leaner, meaner more profitable company that would be controlled by investors.

Critics of this way of doing business call it “corporate raiding” and say the raider adds no value but leaves the surviving company saddled with debt. And because the process almost always involves selling off parts of the company or merging and shutting down operations, workers are left without jobs and communities are hurt by plant closings.

KSL Recreation

In every annual report since KSL Recreation Group was incorporated, company executives have reported to its investors and the public that: “The Company believes that its employee relations are generally good.” The 2002 report goes on to mention that: “Unions represent none of the employees at Desert Resorts, Doral, Grand Traverse or Lake Lanier. At Grand Wailea, one union represents approximately 76% of employees. At the Biltmore, one union represents less than 1% of its employees. At La Costa, one union represents approximately 50% of employees. At The Claremont, three unions represent approximately 51% of employees. The Company is currently engaged in collective bargaining with unions at Biltmore, La Costa and The Claremont.”

Like its parent, KSL has grown by acquiring existing properties. In December 1993, KSL bought the La Quinta and PGA West Resorts in Palm Springs, California, and the Doral Resort in Miami, Florida. There was no union at the resorts in Palm Springs, but the Doral Resort was unionized.

Doral Resort’s unionized workers were terminated and told to reapply for their jobs. Workers were hired from outside the existing workforce and the company went non-union. Without a union contract, management could set its own wages and benefits, which were lower than before. Now, workers need to pass an annual reading, writing and aptitude test to keep their jobs. Doral workers are continuing their attempts to organize, but legal conditions (it’s a right-to-work-for-less state) in Florida make it much more difficult to organize unions.

Claremont’s story

In April 1998, KSL purchased the 279-room Claremont Resort in Oakland, California. The Claremont was also a unionized hotel and KSL planned to go non-union, as it had done in Florida. However, this time, the Claremont workers found out about the sale in advance and mounted a public pressure campaign to protect their jobs. A full-page ad was run in the San Francisco Chronicle and the community responded to help the workers. KSL finally agreed to offer jobs to all the current employees without loss of seniority and full credit for years of service for vacation, sick leave, and other benefits. At first, KSL attempted to negotiate a contract with cuts in wages and benefits, but would later enter into an agreement that would maintain all wages and benefits at the current levels.

When that first contract expired in September 2001, KSL wanted substandard conditions and workers to pay more for family health care. After two years, Claremont workers are still fighting for a fair contract from KSL.

The hotel side was unionized, but 140 workers in the spa operations were non-union. In December 2001, the spa workers attempted to organize a union. KSL responded by running a classic anti-union campaign. By May 2002, conditions became so bad that the unionized workers and the spa workers called for a national boycott of the Claremont Resort. The City of Berkeley passed a resolution in support of the boycott, which continues to this day.

A “Boycott the Claremont Resort & Spa” website describes what guests can expect at the resort: “

Nestled in the hills of Oakland,

—continued on page 8