THE PLANTATION SYSTEM

Sugar and pineapple were big and profitable businesses, and the needs of the industries came to dominate the government and life of the Hawaiian Islands. Sugar was no longer produced by small farmers, but by 33 large-scale plantation operations, each employer hundreds of workers covering thousands of acres of the best agricultural lands.

In the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Report of 1939, James Shoemaker described management attitude towards labor and labor unions:

“Although many of the large enterprises maintain effective employee-welfare policies, their attitude may best be described as benevolently paternalistic rather than liberal. The history of management in Hawaii, broadly speaking, is one of antagonism to labor organization.

“The high degree of intercorporate control makes it possible to mobilize the resources of all large enterprises to restrict the growth of labor unions and to combat strikes in whatever fields of industry they may occur. Thus, although management has done much for labor in Hawaii, it has also used every influence at its command to restrict labor organization.

“The positions of the individual plantation worker is especially vulnerable. The house in which he lives, the store from which he buys, the fields in which he finds his recreation, the hospital in which he is treated, are all owned by plantation management, which in turn has its policies controlled from the offices of the factors in Honolulu.”

Detail from the ILWU mural “Solidaridad Sincidal.” This portion of the second panel depicts a working family before the ILWU organized sugar workers in the 1940s. The family gazes somberly at the meager paycheck that is barely enough to sustain them.

LIVING STANDARDS OF PLANTATION WORKERS

In 1936, Edna Clark Wentworth and Frederick Simplich Jr. studied the living standards of 101 Filipino families on a sugar plantation.

The average family received an annual income of $682.81 which included the earnings of all family members. More than half of the families, 57%, ended the year with an average deficit of $85. Less than half of the families, 43%, ended the year with an average surplus of $99 a year. The average deficit of all families was $8.35 for the year.

By 1939, wages had increased only slightly. The average sugar worker earned about 27 cents an hour, or $587 a year. Most of the plantation families had to spend 50% of their income for food and the larger families were “apt to suffer from malnutrition,” noted James Shoemaker in the 1939 Bureau of Labor Statistics Report on Hawaii.

THE FORMATION OF ILWU LOCAL 142

Hawaii in 1935 was dominated by five companies, known as the Big Five, which owned or controlled nearly all economic activity in the islands. To a large extent, business controlled government and society—the political and social climate was very pro-business and very anti-union. The few unions that did exist were limited to white skilled craftsmen.

In the beginning, organizing efforts were separate and independent. Jack Wayne Hall, a former sailor, helped organize longshore and pineapple workers on Kauai and put out a mimeographed newsletter called the VOICE of Labor. Other union activists such as Harry Kamoku organized longshore workers on the island of Hawaii. Jack Kawano and Fred Kamahoahoa worked to build a Honolulu waterfront union. There were many others involved, but these are some of the more prominent names.

By 1938, these early unions affiliated with the West Coast ILWU as separate locals. When workers first began to organize and join the ILWU, they formed separate locals for each plantation, longshore operation or factory.

Workers in these separate locals discovered they needed greater unity in order to bargain with employers. They joined forces and formed 4 territory-wide locals:

- Local 136-Longshore and Allied Workers of Hawaii

- Local 142-United Sugar Workers

- Local 150-Warehouse, Manufacturing & Allied Workers

- Local 152-Pineapple and Cannery Workers

Even with this greater degree of organization and unity, not all of the locals could afford to open an office or hire full-time business agents or officers.

In 1952, the territory-wide locals merged to form a single, consolidated Local 142. This way, the union gained strength and built island-wide economic and political cooperation.

Consolidation of Local 142 enabled the Union to pool resources and provide more and better services for all ILWU members.

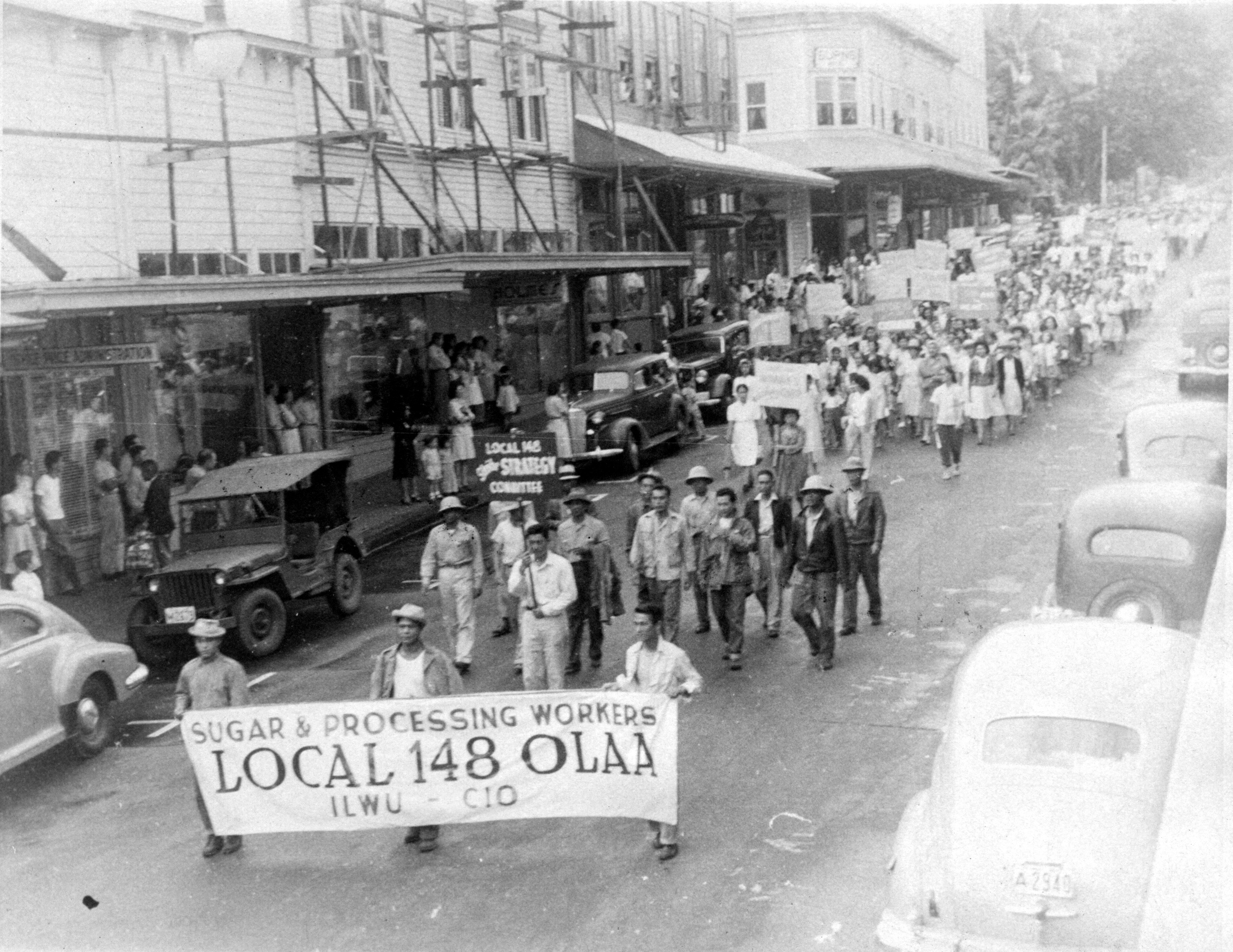

THE 1946 SUGAR STRIKE

The 1946 Sugar Strike was more than a labor-management dispute, it was a turning point in the social and economic revolution that would transform Hawaii from an almost feudal plantation society to a modern, democratic state. Hawaii’s 28,000 sugar workers were struggling to bring dignity and fairness to their working lives by organizing into a union, the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) Local 142. Their successful organization would change the course of Hawaii’s history.

In 1946, Hawaii was dominated by a privately owned plantation system where over 100,000 people, one-fifth of the population, lived and worked. The plantations and nearly every other major economic activity in Hawaii was controlled by five companies, which in turn were controlled by a few wealthy families through a network of intermarriages and stock ownership.

While the plantation owners reaped fabulous wealth from the $160 million annual sugar and pineapple crop, workers earned 24 cents an hour. The plantations devised a system of labor control after ruthlessly breaking attempts by three generations of sugar workers to improve their wages and conditions. The plantations learned to divide workers by recruiting different nationalities and housing them in separate plantation camps. Workers were kept on the plantations through wages and by creating a dependency on plantation controlled stores, housing, medical clinics, and social facilities.

The sugar workers also learned lessons from the past. The union organization brought workers together and called on each individual to share their skills, talent, and energy for the good of the whole.

The union united the different ethnic groups by actively fighting racial discrimination and recruiting leaders from each group. Members were kept informed and involved through a democratic union structure that reached into every plantation gang and plantation camp. Every member had a job to do, whether it was walking the picket line, gathering food, growing vegetables, cooking for the communal soup kitchens, printing news bulletins, or working on any of a dozen strike committees.

In the course of winning their strike, sugar workers received a crash education in organization, leadership, political economy, and civics. The power of unionization and this new found knowledge changed the lives of 28,000 sugar workers and their 47,000 family members. A year later, the struggle spread to involve 20,000 pineapple workers and thousands of their family members. The union movement had spread too far and too wide to ever be contained again. The plantation stranglehold on Hawaii’s economy and social life was ended, and this opened the way for Hawaii to develop into a modern, democratic society.

1949 DOCKWORKERS FIGHT FOR PARITY

The following is reproduced from the UH Center for Labor Education and Research (CLEAR) website. CLEAR produced a video on the 1949 dock strike under its “Rice and Roses” production banner.

By Dr. William J. Puette

Why was the 1949 Dock Strike so important?

The 1949 longshore strike was a pivotal event in the development of the ILWU in Hawai’i and also in the development of labor unity necessary for a modern labor movement. The 171 day strike challenged the colonial wage pattern whereby Hawai’i longshore workers received significantly lower pay than their West Coast counterparts, even though they worked for the same company and did the same work.

While wage parity was the major bargaining issue, the strike marked a last ditch attempt by the Big 5, a group of five companies that dominated Hawai’i, to break the strength of organized labor. The strike had major ramifications beyond Hawai’i and had an impact on Congressional deliberations regarding statehood.

In the years after World War II, the United States waged an undeclared “Cold War” against the Soviet Union and their socialist allies. U.S. capitalism even attacked unions and any form of solidarity as un-American and a mortal threat to private profit. Militant unions like the ILWU were singled out for attack and union leaders were branded as members of a communist conspiracy.

This “Red Baiting” reached a fever pitch with both Hawai’i and national papers accusing the ILWU of working for Joe Stalin of the Soviet Union. Hawaii’s Legislature passed the Dock Seizure Act. Wives of company executives and managers, marching as the “Broom Brigade,” demonstrated against the ILWU pickets and management propaganda projected starvation for Hawai’i.

With steadfast rank and file members, brilliant leadership, and superb organization, the ILWU was able to prevail against this formidable array. To achieve victory, the ILWU attracted solid community support and a unified labor movement. Images of Jack Hall and Arthur Rutledge on the same picket line convey this sense of shared commitment. The ILWU made effective use of its own media weapons with both English language and Filipino radio programs as well as the labor and ethnic press.

The story of the 1949 dock strike will be anchored by the faces and voices of the rank and file longshoremen who were the heroes of 1949. The reality of the times will be captured through the stories of the people who made this history. Interviews with dozens of people were conducted on O’ahu, Maui and the Big Island as the CLEAR Researchers collected film, photos and visual images. Scripts from Bob McElrath’s radio broadcasts will be dramatized to convey the issues and capture an authentic feel. Authentic voices from the other side of the strike will also be utilized to convey the sense of drama and conflict which were part of the era.

In a very real way, Hawaii’s labor movement confronted the phenomenon now known as globalization, long before the word began being applied to current events. These labor pioneers showed that unity was a real weapon in the fight for dignity and fair treatment. The telling of this story can point to answers for present problems and as it showcases the ordinary men and women who were able to muster extraordinary resources to achieve victory.

SIX DECADES OF MILITANT UNIONISM

THE ILWU STORY – SIX DECADES OF MILITANT UNIONISM

Chapter 4: Organization in Hawaii

The following is an excerpt from The ILWU Story on the ILWU in Hawaii. To read more, order your own copy directly from the International office or call your Business Agent to see if copies are available at your Division Office. Or visit the ILWU International website to read more online.

“The ILWU’s principles of rank and file unionism have never been more severely tested or more magnificently successful, than in Hawaii-where over half the U.S. membership of the ILWU lives and works. The union’s victories were achieved after 100 years of bitter experience and sacrifice by Hawaii’s workers, successfully resisting terrible repression by many of Hawaii’s most powerful employers and government officials.

“Five big landholding companies controlled the economy of the Territory of Hawaii. Their interlocking directorates and close cooperation allowed them to act as one great combine that dominated the Territorial government and every aspect of the Islands’ political, economic, an cultural life.

“When the Big Five took over the bulk of the arable land of the islands in the early 1800s, they destroyed the traditional economy and set up a plantation system that forced most workers to live in company housing and work the plantations for miserable wages, under brutal working conditions.

“The employers dealt severely with protesters and smashed every attempt workers made to improve their conditions. They encouraged racial divisions and suspicion to the point that when the workers sought to organize into unions, they made the tragic mistake of following racial lines.”