A weak economy, accounting irregularities like overstating profits, too much debt, and growing too rapidly has led to record levels of corporate bankruptcies in 2001 and 2002. There were 257 corporate bankruptcies in 2001, a record for the largest number of bankruptcy filings in a single year. In 2002, there were only 187 filings but the value of the assets involved, $368

billion, set a new record. Five of the 10 largest bankruptcies of all time occurred in 2002—WorldCom, Global Crossing, Kmart, Conseco, Adephia Communications, and UAL Corp. Two of the largest occurred in 2001—Enron and Pacific Gas

and Electric.

Like falling dominos, the failure of corporate giants sends a ripple effect through the economy that can bring down other

companies and change the lives of tens of thousands of workers. Economist predict that many more companies will go

down in 2003 as the result of the bankruptcies of 2001 and 2002.

That ripple effect has finally caught up with 140 ILWU members at Fleming Hawaii, who now face a new and uncertain future as Fleming Companies Inc. finalizes the sale of its wholesale grocery business in an effort to reorganize under a Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

A slowdown in the grocery business, credit and financing problems, and the loss of its biggest customer—Kmart—led to a complete turn around in the economic fortunes for Fleming, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on April 1, 2003. To cut

costs, the company plans to focus on its core business as a package goods distributor and sell off its retail stores and wholesale grocery operations.

On July 8, 2003, Fleming signed a purchase agreement to sell its wholesale grocery business for $400 million to C&S Wholesale Grocers. C&S is the 11th largest privately owned company in the U.S. with 7,500 employees and revenues

around $9.7 billion. The sale includes the Hawaii operation and a Fleming center in West Sacramento where 350 workers are represented by ILWU Local 17 and Teamsters Local 150. The sale is subject to the approval of the Bankruptcy Court.

Change of fortune

Two years ago, the Texas based Fleming Companies Inc. was riding high as one of the nation’s largest wholesale food and package goods distributor, supplying over 7,000 supermarkets, convenience stores, and supercenters with merchandise. Business was good and the company was growing rapidly—annual sales was over $15 billion and increasing by the billions, profits were up, and the company was paying dividends to its stockholders. In February 2001, Fleming thought it hit the jackpot with a 10-year deal worth $4.5 billion as the primary supplier of food and consumable products for all2,100 Kmart stores. Kmart quickly became Fleming’s largest and most important customer and accounted for 20 percent of Fleming’s business. But within a year, in January 2002, it became clear that Kmart was in serious financial trouble when t failed to make a weekly payment of $76 million to Fleming for merchandise already delivered. On January 21, 2002, Fleming announced it was temporarily suspending shipments to Kmart. The next day, Kmart filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and petitioned the

bankruptcy court to authorize payment of the $76 million owed and to name Fleming a critical vendor. Fleming resumed shipments and would continue to supply Kmart stores.

To cut costs, Kmart looked at its 2,114 stores and simply closed down 323 stores that were under performing and not meeting

profit requirements. Over 25,000 workers will lose their jobs. Kmart also reached an agreement with Fleming to terminate their 10-year supply agreement as of March 8, 2003. Fleming had initially sought $1.5 billion in damages but settled for about $37 million in cash and $350 million in Kmart stocks. Kmart emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy on May 5, 2003.

The termination of the Kmart contract had a major negative impact on Fleming, and the company was forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on April 1, 2003.

What is a Chapter 11 Bankruptcy?

There are two ways a company can declare bankruptcy under U.S. laws—Chapter 11, where a company tries to recover from crippling debt or Chapter 7, where a company goes out of business.

If a company declares bankruptcy under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, it will attempt to reorganize. The company is protected from its creditors but must have a plan to pay back the debt and become profitable. Management may continue to run the day-to-day business operations, but the bankruptcy court must approve all significant business decisions.

A company also can file for bankruptcy under Chapter 7 if it intends to stop all operations and go completely out of business. The bankruptcy court will then appoint a trustee to liquidate the company’s assets to pay off the debt, which may include debts to creditors and investors.

Workers need protection

ILWU members at Fleming are lucky they are organized and have a union, because a union is usually the only protection American workers have when a business changes ownership. Being unionized gives Fleming workers the right and power

to bargain over their wages, benefits, and conditions of employment with both their former employer and the new employer. This benefits both the new employer and workers by making the transition as smooth as possible.

Surprisingly, non-union workers have little or no rights when a company changes ownership. The new owner buys the business and material assets, not the workforce. The new owner can hire a completely new workforce and all the existing

workers can lose their jobs. In addition, even if the former workers are retained, the new owner can change wages, benefits, and working conditions and ignore a worker’s seniority.

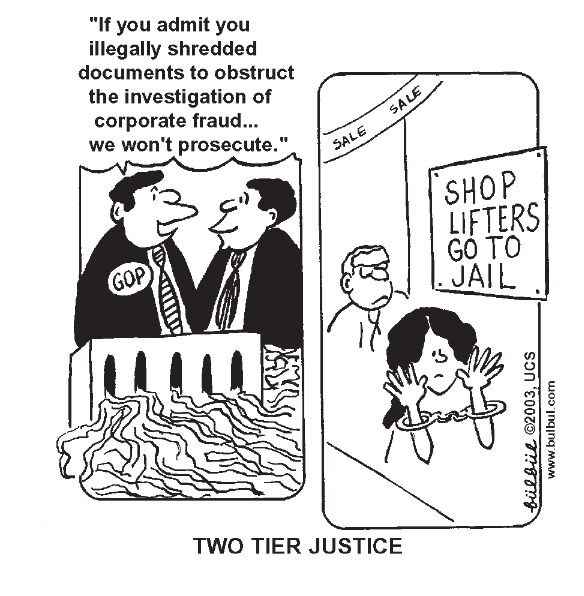

While many European countries have many laws that protect workers, the U.S. has no law that requires a new owner to retain any part of the old workforce. ILWU attempts to get such legislation, in the form of SB364 introduced by Senator Brian Kanno, have not been successful and have been strongly opposed by the Republicans in both the House and Senate.

Better bankruptcy laws needed ILWU members have learned through bitter experience that bankruptcy laws fall short in protecting workers’ economic interests. Under current law only a small portion of wages and benefits owed toemployees is given priority over other unsecured creditors—the amount is capped at $4,650 and only reaches back to the 90-day period

prior to a company’s filing for bankruptcy—and wages, severance, vacation, and other benefits owed to employees above this

cap is given low priority as a general, unsecured claim.

Because of this cap, members with high seniority at Grayline Hawaii received only a portion of what the bankrupt

company owed them. More recently, the union has been helping members at the Hawaiian Waikiki Beach Hotel in their

claim for money owed them from bankrupt Otaka, Inc.

A resolution passed by the 30th ILWU International Convention in San Francisco, urged ILWU members—“to be vigilant of their own employers concerning the timely payment of insurance bills, pension contributions, and union dues checkoff, particularly when employers are experiencing financial difficulty; and . . . to work for legislation that requires successor employers to retain all workers and to recognize and bargain with the incumbent union.”

Members can safeguard their own interests by alerting the union when their employers appear to be in financial trouble.