The King holiday is unique in that it brings together people of all nationalities and faiths to do something to make the world a better place. This year’s theme, “Remember! Celebrate! Act! A Day On, Not A Day Off!!”, urged Americans to use the holiday as a day of service to humanity.

LWU members and retirees were among the thousands of marchers who paraded through Waikiki on January 15, 2007 on the national holiday named after slain civil-rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. Many of the marchers held signs calling for “Peace” and an end to the war in Iraq.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was assassinated at the age of 39 on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee. King was in Memphis supporting 1,300 city sanitation workers who were on strike for their dignity and an end to racial discrimination.

Now let us maintain unity

King told a rally of 2,000 workers and their supporters at the Mason Temple on April 3, 1968:

You are demanding that this city will respect the dignity of labor. So often we overlook the work and the significance of those who are not in professional jobs, of those who are not in the so-called big jobs. But let me say to you tonight that whenever you are engaged in work that serves humanity and is for the building of humanity, it has dignity and it has worth.

“And that’s all this whole thing is about. We aren’t engaged in any negative protest and in any negative arguments with anybody. We are saying that we are determined to be men. We are determined to be people. We are saying that we are God’s children. And that we don’t have to live like we are forced to live.

“Now, what does all of this mean in this great period of history? It means that we’ve got to stay together. We’ve got to stay together and maintain unity. You know, whenever Pharaoh wanted to prolong the period of slavery in Egypt, he had a favorite, favorite formula for doing it. What was that? He kept the salves fighting among themselves. But whenever the slaves get together, something happens in Pharaoh’s court, and he cannot hold the slaves in slavery. When the slaves get together, that’s the beginning of getting out of slavery. Now let us maintain unity.

“Secondly, let us keep the issues where they are. The issue is injustice. The issue is the refusal of Memphis to be fair and honest in its dealings with its public servants, who happen to be sanitation workers. Now, we’ve got to keep attention on that.

“Now we’re going to march again, and we’ve got to march again, in order to put the issue where it is supposed to be. And force everybody to see that there are thirteen hundred of God’s children here suffering, sometimes going hungry, going through dark and dreary nights wondering how this thing is going to come out. That’s the issue. And we’ve got to say to the nation: we know it’s coming out. For when people get caught up with that which is right and they are willing to sacrifice for it, there is no stopping point short of victory.”

A sniper’s bullet

The next evening while King was leaving his motel room to attend a meeting to plan another march to support the workers for April 8, he was killed by a sniper’s bullet, fired by James Earl Ray. After King’s death, President Lyndon Johnson sent federal troops to keep order and Undersecretary of Labor James Reynold to mediate a settlement between the union and Mayor Loeb.

40,000 march

On April 8 the march went on as scheduled. Mrs. Coretta Scott King took the place of her fallen husband, and 40,000 people marched through downtown Memphis in support of the striking workers and in tribute to Martin Luther King. Sixtyfour days after the strike began, on April 16, 1968, the union announced that a settlement was reached and the strike was over. The city would recognize the union, increase wages by 15 cents, make merit promotions without regard to race, and ban racial discrimination.

King’s death helped bring an end to the strike, but the struggle of the Memphis sanitation workers had already grown to become a movement. The striking workers had broad support within the black community, religious leaders of all faiths, and the labor movement. There was a black boycott of downtown businesses. There were daily marches in support of the workers, and numerous demonstrations and vigils at city hall. Students and entire congregations were joining the marches. Hundreds of workers and their supporters were being arrested for acts of civil disobedience. Over 10,000 people attended a rally on March 14, and 17,000 attended a rally on March 18 when Martin Luther King first came to Memphis.

Dignity at work

Today, the conditions of Memphis sanitation workers have been transformed. Instead of working six days a week, they now work five. Before, they worked as long as it took to bring in the garbage, with no extra pay; now they work 8-hour shifts and are paid overtime. Before, they had no breaks; now there are two 15-minute breaks and time for lunch. Before, white supervisors could fire black workers on a whim; now they have a grievance procedure and there must be just cause to fire someone. With union collective bargaining, their wages and benefits have steadily improved.

For the Memphis sanitation workers, their struggle to unionize went hand in hand with the struggle for civil rights and justice. ◆

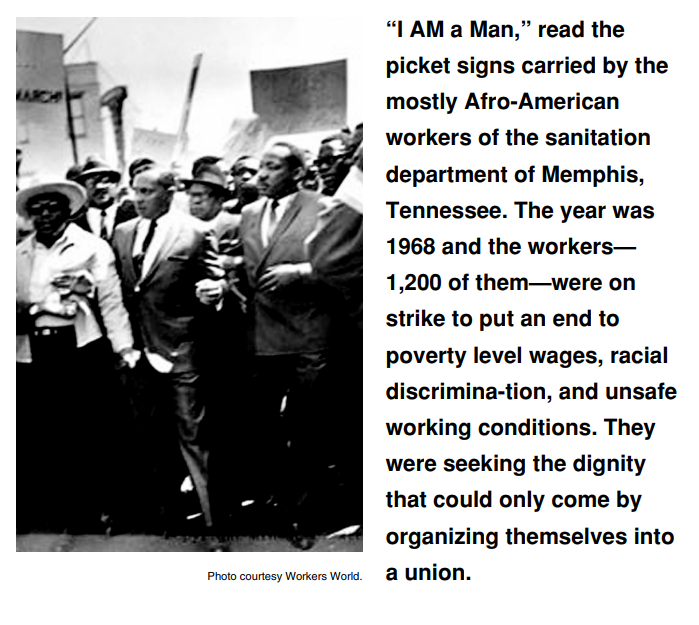

“I AM a Man”—unions bring dignity and respect to

workers

The slogan on their signs carried many meanings. It was a statement that they were human beings, who would not be treated as inferiors or forced to live in poverty. They wanted decent wages so they could support their families with dignity. It was a statement that they were adults, not children, and they would decide on their own to join a union instead of relying on the city to “take care of them.” It was a statement they were men, and would no longer be called “boys” and treated like personal servants by their white supervisors.

The workers had been trying to organize as the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Local 1733 union since 1963. The city refused to recognize the union, but the workers continued to take their grievances to management. They were led by T.O. Jones, a refuse worker who was fired for union activity. They protested the lack of maintenance and broken down trucks assigned to black workers. They objected to the preferential treatment of white workers and the arbitrary treatment of black workers. They complained about the terrible working conditions and lack of benefits, and their average wage of $1.80 an hour was so low that even after working full-time, many of the workers still qualified for welfare.

Crushed and killed “like garbage”

During a heavy rainstorm on February 1, 1968, two black sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, had climbed into the back of their garbage truck to stay dry. An electrical short triggered the compactor mechanism and they were crushed and killed. “Like garbage,” complained their fellow workers. The Memphis Sanitation Department gave the families of the slain workers a month’s pay plus $500 which barely covered the $900 burial expense. As unclassified, hourly employees they were not covered by workers compensation and their families were left destitute.

Earlier that the same day, 22 black sewer workers had been sent home with only two hours pay. Under newly elected Mayor Henry Loeb, the sanitation department revived an old practice where black workers could be sent home on rainy days. White workers, who held the supervisory positions, stayed on the job with full pay.

ILWU members, retirees, family and friends joined other union and community members in a march to celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King’s life on January 15, 2007. The principles guiding Dr. King’s work were very similar to the principles guiding our union, and he became an honorary member of the ILWU Local 10 in 1967.

The black workers were outraged and 1,200 walked off the job on February 12, Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. They wanted the city to recognize their union, a grievance procedure, and an end to racial discrimination. They wanted to be recognized as human beings. ◆