Hawaii will be celebrating the 100 year anniversary since December 20, 1906, when the first group of 15 men from the Philippines arrived in Honolulu aboard the S.S. Doric. They were dispatched the following day to work for the Ola’a Plantation on the Big Island, a new and very large plantation that needed all the laborers it could get.

Over the next forty years, until 1946, a total of 125,917 Filipinos were brought to Hawaii by the Hawaii Sugar Planters’ Association (HSPA) to work on the sugar plantations that were expanding on every island and in every area where land and water could be found. The Filipinos were called Sakada, the Visayan word for seasonal farm worker, and their story is truly remarkable.

The Sakada braved unknown conditions and hardship to take jobs in a foreign country, thousands of miles away from their birthplace in the Philippines. They endured long hours of backbreaking work, so they could send a little money home to help support the families they left behind.

From the beginning, the Sakadas stood up against injustice by joining with other plantation workers to improve their wages and working conditions. They joined and organized labor unions. Many rose to positions of top leadership within the unions. All six presidents of the ILWU Local 142 were Sakadas or their descendants: Antonio Rania, Calixto “Carl” Damaso, Erinio “Eddie” Lapa, Eusebio “Bo” Lapenia, Jr., and Fred Galdones.

Thanks to higher wages and better conditions brought about by unionization, Sakadas were able to send substantial sums of money to their families in the Philippines. With better retirement benefits, many Sakadas were able to return to the Philippines and live a very comfortable life.

More than half of the Sakada returned to the Philippines or moved on to find work on the Mainland. Those who stayed became part of the multi-ethnic community that makes Hawaii unique in the world. The 2000 Census counted 170,635 Filipinos and another 105,728 part-Filipinos in Hawaii.

The Sakadas can be proud of their accomplishments in making a living for themselves and the tremendous contributions they made to improve life for their families in the Philippines and in Hawaii.

Labor Shortage

As early as 1901, Hawaii sugar planters were looking to the Philippines for the thousands of laborers the industry needed to expand production to meet the increasing demand for sugar. US laws prohibited any further importation of Chinese laborers, and the Japanese were leaving the plantations by the thousands. Those who stayed were getting more aggressive in demanding better housing and higher wages. In 1900 alone, there were 20 strikes involving 8,000 workers. These early efforts were spontaneous and unorganized—workers did not try to form any kind of permanent organization.

To keep their workers, plantations increased wages from $12.50 a month to $15 a month, and as high as $22 a month in remote areas. Because of the severe labor shortage, some plantations would try to entice workers away from neighboring plantations by offering a slightly higher wage. The Hawaii Sugar Planters’ Association (HSPA) put a stop to this practice in 1901 by setting a maximum wage plantations could pay workers of $18 a month in most areas and $24 a month in remote areas.

In July 1906, the HSPA was granted special permission from the Philippine Commission (the colonial governing body appointed by the US president) to recruit laborers and to land ships in various ports to take or return the laborers. As both Hawaii and the Philippines were territories of the United States, there were no restrictions on the number of Filipinos who could be brought to Hawaii.

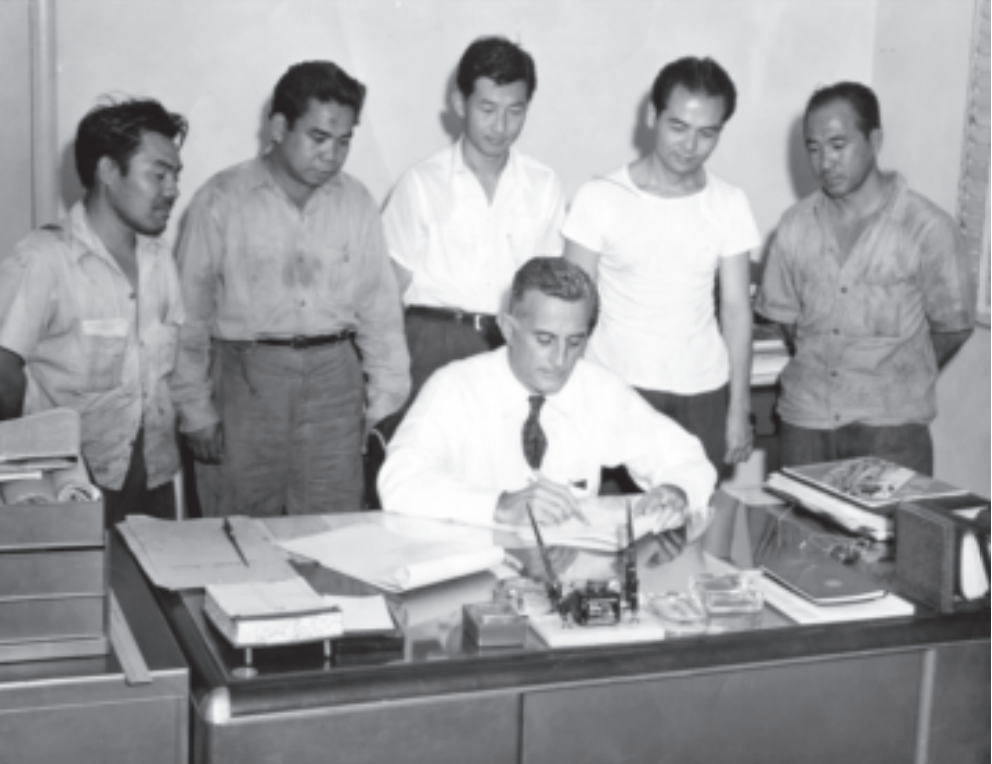

The sakada played a critical role in winning the 1946 sugar strike—a strike in which the power of unionization chnaged the lives of 75,000 Hawaii sugar workers and their families. (Above) Sigining the agreement after the 1946 sugar strike in Kekaha: Shigeyoshi Agena, Prudencio Dela Cruz, Kenjo Kimoto, a plantation manager, Constancio Alesna, Fred Taniguchi.

By 1910, the HSPA had recruiting centers in Manila, Cebu, Iloilo and Bohol and was sending 3,000 workers a year to Hawaii. The sugar planters had just defeated a strike of 7,000 Japanese workers on Oahu by hiring other ethnic groups to replace the Japanese. The Japanese made up 71 percent of the plantation workforce and were getting better organized. By importing large numbers of Filipinos, the planters could create a divided and more controllable workforce.

Mostly Visayans

The early recruits came mostly from the Visayan Islands, where the population was poor and farmed land as tenants or found work as sakada on huge sugar haciendas. Like Hawaii, a small and wealthy elite class and their descendants controlled the wealth and owned most of the land in the Philippines.

The Visayan sakadas had a threeyear contract with the HSPA where they agreed to work 10 hours a day and 26 days a month. In return, they would be paid $16 a month and receive free transportation to Hawaii, housing; water, fuel, medicine and health care. Their pay would increase to $17 a month in the second year and to $18 a month in the third year. A total of $72 was deducted, $2 a month, to pay for their return fare to the Philippines.

In the 1920s, the HSPA shifted their recruiting to the Ilocos area on the northwestern coast of the Luzon Islands. In Hawaii, the Visayans were organizing unions and demanding better conditions. In 1920 they Honoring the Filipino Sakada, Part I Hawaii will be celebrating the 100 year anniversary since December 20, 1906, when the first group of 15 men from the Philippines arrived in Honolulu aboard the S.S. Doric. They were dispatched the following day to work for the Ola’a Plantation on the Big Island, a new and very large plantation that needed all the laborers it could get. formed the Filipino Labor Union and coordinated their protests with Japanese workers organized in the Japanese Labor Federation. Visayans were also getting harder to recruit, because homesteads were opening up in Mindanao, and word was getting out that Hawaii was not the “Land of Glorya” described by HSPA recruiters. The planters also saw an advantage in dividing Filipinos by language, since the Ilocanos and Visayans spoke different dialects.

Ilocano majority

Recruitment of Ilocano sakadas increased and sometimes exceeded 10,000 workers a year. By 1932, the plantation workforce of 50,000 was 70 percent Filipino and mostly Ilocano. The next largest group was the Japanese (9,395 workers), followed by the Portuguese (2,022). The rest were Caucasians, Puerto Ricans, Chinese, Hawaiians, and Koreans.

In 1934, the US granted the Philippines a degree of independence and Filipino immigration was limited to 50 a year. This was not a problem for the sugar industry as nearly all the available land in Hawaii had been turned into sugar and pineapple fields, and there was no need for additional workers.

There were no further recruitment of sakada until 1946, when the sugar industry, now controlled by five giant corporations, claimed there was a labor shortage and got an exemption to bring 7,361 Ilocanos to Hawaii— 6000 men and 1361 women and children. It was a deliberate move to break the growing union movement in the sugar industry. ◆

Next month: Honoring the Sakada, Part II Racial unity and the 1946 strike