Back in the day, locally owned coffee companies lined the streets facing San Francisco’s waterfront. Longshore Local 10 members literally rolled sacks of beans across the street for roasting and shipping by warehouse Local 6 members.

Now just one of those local coffee companies remains, and it has moved to Oakland.

Light manufacturing has gone the way of coffee and the Warehouse Division has hemorrhaged members up and down the Coast. Longshore work has changed as well, though membership has held steady.

“Containers are stuffed and unstuffed overseas or off-dock and all the handling work we did is gone,” ILWU International Vice President Bob McEllrath said. “All we do is move boxes from ship to dock to rail.”

For the last ten years the ILWU has been engaged with organizing, trying to balance the loss of work and members. The union took another step in deepening that commitment Dec. 8, when the first meeting of the Elected Leaders Organizing Task Force brought most of the mainland IEB members together with officers from warehouse locals and ILWU organizing staff. Top organizers from the national AFL-CIO flew in to huddle with the Task Force and plan for these times that make organizing more urgent and more challenging than ever.

“We were pleased to have the AFL-CIO’s national Organizing Department come in and help set a course and pinpoint strategies that will strengthen the ILWU in our key industries,” McEllrath said.

This followed a workshop done by the AFL-CIO for Local 142 in June, International Vice President Wesley Furtado said. “We had 50 rank-and-filers there along with 25 officers and the International organizers,” Furtado said. “We have already seen that training bear fruit.”

The ILWU’s International Convention in 1994 committed the union to an organizing policy, but did not budget for it. Later that year, the Titled Officers proposed that each mainland member put in $2 per month for two years to fund the new direction. The “2- 4-24” assessment, as it was called, passed in a mailballot referendum. The 1997 Convention upped the ante, earmarking 30 percent of the International’s budget for organizing. The organizing program tried out different structures and took on a wide range of targets. Drawing on past experience, participants in the Dec. 8 meeting took a hard look at the present and future.

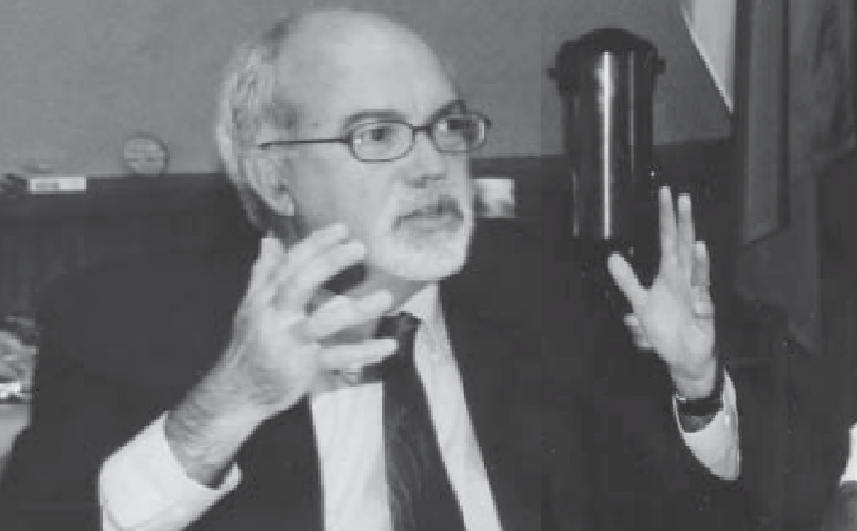

ILWU Organizing Director Peter Olney (standing) presents the union’s strategic organizing perspective. Looking on (l-r) clerks’ Local 34 Vice President Frank Reilly, warehouse Local 6 Secretary-Treasurer Fred Pecker, and Robert Masciola and Ken Zinn of the AFL-CIO’s Center for Strategic Research.

“We have three points to consider as we think about organizing today,” ILWU International Organizing Director Peter Olney said. “We have to do it now, we have to do it smart and we have to do it together. We have to do it now because the labor movement and the ILWU are watching their density decline. We have to do it smart, using leverage and selecting targets that fit with our strategic vision. We have to do it together, as we need the participation of elected leadership and membership.”

Do it now

“We are in very real danger,” AFL-CIO Organizing Director Stuart Acuff told the Task Force. “Unless we get very drastic, very quickly, we could be the first generation to leave our children a lower standard of living and less justice.

“When did you go into bargaining thinking, ‘We’re going to make major gains?’ It’s very rare, because only 12.8 percent of all workers in this country belong to unions, 8.2 percent of workers in the private sector,” Acuff said. Union density, the percent of workers in an industry or an area who belong to unions, has everything to do with quality of life for workers, in or out of unions. Organizing to increase density benefits current members when they enter bargaining as much as it benefits new members getting their first contract. It creates what Acuff called a “virtuous circle.”

Before SEIU’s Justice for Janitors campaign took off, most janitors worked part-time for low or minimum wages and no benefits, according to Robert Masciola of the AFL-CIO’s Center for Strategic Research, who also attended the Dec. 8 meeting. Over 10 to 12 years, JforJ organized up to 90 percent of the cleaning companies in some cities. It pushed wages up to around $10 per hour, won benefits and spread from cities to surrounding suburbs.

“In 2003, where we had the most strength we were able to get family healthcare for our members,” Masciola said. Truckers saw the opposite happen. In 1979, with union density at 50 percent, unionized truckers enjoyed average wages of $19.56 per hour. Density dropped by half over the next 27 years, and average union wages fell by almost $6 per hour, by AFL-CIO figures.

Warehouse workers still under contract need to watch out, warehouse Local 6 Secretary-Treasurer Fred Pecker said. “We’re making close to $18 an hour under our master contract,” said Pecker. “Non-union warehouse workers make $8 to $15 an hour and their benefits aren’t near ours. But this is a big drag on us in negotiations and everywhere else. Our members need to see their families aren’t secure as long as these gaps exist. A rising tide lifts all boats, but a falling tide pulls everyone towards the drain.”

AFL-CIO Organizing Director Stuart Acuff explains how union density, having more workers in an industry, helps all workers.

Many members in the ILWU’s Warehouse Division—like those from Max Factor and Rite-Aid, Folder’s and Colgate—know up close the story the statistics tell. Union density in West Coast warehousing plunged from 31 percent in 1983 to 14 percent in 2003. But the Longshore Division’s share of the work is slipping too, according to research done for the ILWU by the Institute for Labor and Employment at the University of California.

The number of registered longshore workers has held steady over the last 20 years, while overall employment in the cargo-handling industry has exploded. Highly unionized parts of the industry, like railroad and water transport, have been shrinking. Less unionized sectors like warehouse have been growing rapidly.

Do it smart

Organizing can build density, but only if unions get smart about how and where they do it. Relying on elections supervised by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) saddles them with skewed rules enforced by a Board stacked with Bush appointees.

“The U.S. ranks among the top four violators of workers’ right to organize, right up there with Colombia and China,” Acuff said. Almost all workers face antiunion campaigns when they try to organize and some 20,000 get fired each year for their efforts. The firings are illegal, though the campaigns are not, and the law provides neither deadlines to encourage timely justice nor strong penalties to discourage violations. One-third of all workplaces that win NLRB elections never get a first contract.

“Unions simply have to refuse to play by rules designed to make them lose,” said Ken Zinn, director of the AFL-CIO’s Center for Strategic Research. They can’t just file for elections with random groups of workers who come to them. Instead, they need to carefully choose targets that build power in their industries and offer opportunities to leverage recognition.

“Leverage comes through understanding and exploiting the employer’s web of relationships with suppliers, customers, competitors, politicians, government regulators, financial institutions, the general public and its own workers. Often the union can exert its greatest leverage on an employer through existing contracts.

“It’s got to be a priority of the union to put organizing front and center in collective bargaining, and make tracking work a priority,” Zinn said. CWA, for example, began “bargaining to organize” as its employers expanded into the wireless business. Only a third of the workers at Verizon Communications belonged to CWA four years ago. A 17-day strike by 37,000 Verizon workers secured the employer’s agreement to be neutral during future CWA organizing efforts.

International Vice Presidents Wesley Furtado and Bob McEllrath with AFLCIO Organizing Director Stuart Acuff.

Through the ILE research, the ILWU has begun to see where its work is going. Peter Olney gave the Task Force a snapshot of the Institute’s work, which shows the cargo-handling industry in rapid transition. Most of the companies in the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA) used to stick to one function. (The PMA is the employer group of steam ship operators and stevedoring companies that negotiate with the Longshore Division.) Shippers carried good across the ocean and dumped them on the dock. Deregulation and technological change have forced these companies to diversify if they want to remain competitive. Most now have spin-offs that operate distribution centers, handle paperwork and planning, and even run trucking lines and airfreight services.

“I knew our employers have become diversified,” said John Tousseau of marine clerks’ Local 63. “But when you get into more depth about the sub-companies of the sub-companies, it’s really eyeopening,” he said.

The union not only needs to follow where cargo goes, but where it comes from said IBU Secretary-Treasurer Terri Mast. “We need to look at all the companies, all the players and understand how cargo is shifting away from the ILWU,” Mast said. “We need a deeper analysis of where the whole maritime industry is heading.”

Do it together

“Plans are nothing, planning is everything,” Zinn said, quoting General Eisenhower.

“The best plan Peter [Olney] can come up with will not be as good as what you can do as a group. Strategic organizing has to make use of the union’s biggest resource—its members,” he said.

Task Force participants quickly rattled off some of the contributions members make to organizing. They furnish the power for actions, energy to add to limited staff, experience in the industry, connections in the community and the most credible voice possible to speak for the union.

The ups and downs of the last several years have shown that day-to-day, effective collaboration will depend on the locals and the Organizing Dept. setting clear goals and commitments and keeping communication open.

Making strategic organizing work will require a vision of the union’s future shared across all divisions.

“We’ve talked about organizing and earmarked money for it, but lots of people in the Longshore Division weren’t seeing what it has to do with them,” Tousseau said. “But we have to protect our flanks, and these other divisions are all part of the ILWU.”

Much of the information shared during the Task Force meeting appears in a PowerPoint presentation, which local leaders and the organizing staff will bring to members as campaigns develop in their areas.

“This was the best meeting I’ve been to for 20 years,” warehouse Local 26 President Luisa Gratz said as the Task Force wound down. “Local 26 lost a fifth of its membership when the company I came out of moved to South Carolina in 1982. I wrote resolutions on organizing for every convention after that. Now, for the first time in a long time, I feel we have a future.” ◆

If you are interested in helping with organizing call your division office or contact the organizing dept. at (808) 949-4161