Hope after HC&S closure

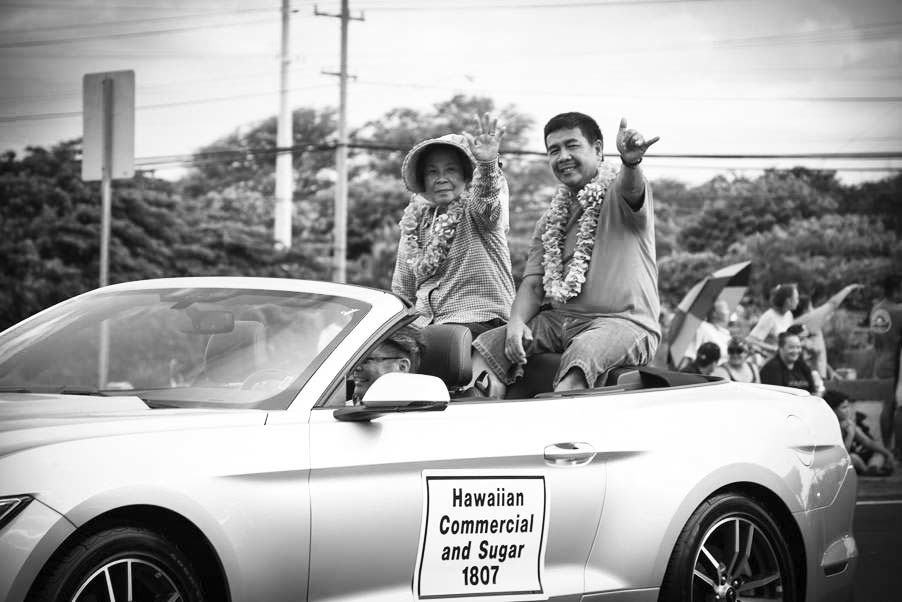

PUUNENE—“Look. I want to show you this,” Fely Corpuz says as she rifles through a care-worn photo album. “Me at the first parade,” she says, smiling as she looks at a photo of herself in a ti leaf-trimmed float for HC&S. “Me at the last one.” She turns to the last page in her album to show the picture on the right and sighs. But continues to smile.

On December 12, 2016, Unit 2101- Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Co (HC&S) made a symbolic day out of their last haul. After 145 years in operation, HC&S completed its 144th and final harvest.

The large crowd, most wearing shirts and hats bearing messages like A Hui Hou, HC&S: 1870-2016 and Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Co: Real People Real Values stepped firmly into the mud to get their last pictures with the tournahauler adorned with lei.

“I never thought this closure would happen in my lifetime,” said Willie Kennison, former ILWU Business Agent for HC&S and Maui Division Director. “Before when other plantations shut down, HC&S would grab ‘em and absorb their loss. The skilled workers will be fine, but my concern is the older laborers. I feel for them.”

When the ILWU first unionized sugar workers from 1944 to 1945 there were 33 plantations, with 25,000 workers. Most of the workers were laboring in the fields cutting cane by hand, but by 1970, less than 10,000 workers were doing the work that 25,000 had done in the 1940s because of increased mechanization.

Education vs. the economy

Technological advancements cut the need for as many workers. Fortunately, however, Hawaii kept up with the technology and the workers adapted and learned the skills they needed to work it. Ben Wilson, unit bulletin editor reflected, “The sugar plantation with all the technology it needed was a very educationbased industry. The company provided education and training so people could get apprenticeships, learn trades.”

Parade Grand Marshal Fely Corpuz and Beato Vercelluz Jr. aboard the last HC&S float in the 94th Maui Fair parade October 2016.

“It was very attractive to stay here on Maui,” said Charles Andrion, a third generation HC&S worker. “I didn’t go to college, but HC&S provided on-the-job training and I was hired as an instrument technician. My grandpa was so happy to learn I would be moving home to work at HC&S like he did back in the day.”

Unfortunately, even education could not edge out the economy. Foreign sugar companies began using the same cane varieties, cultivation techniques, and machinery, while paying their workers a fraction of the wages paid in Hawaii. In 1994, the passage of the so-called free trade agreement with Canada and Mexico, began to open the U.S. market to foreignproduced sugar.

Union contracts alleviate economic blows

HC&S’s workers continued to be paid well through the very end, even as the global market gained a competitive edge over Hawaii’s sugar. Why? Because of the collective bargaining ILWU and the workers did together.

Through collective bargaining, ILWU sugar workers earned higher wages and better benefits than any agricultural worker in the US or world, but Hawaii sugar companies could still compete with sugar coming from countries where workers were paid less than one dollar a day.

“The union, by getting better wages for its members here, created a quality of life. So I guess you can say when the union goes away, the quality of life goes away. Plantation culture became a culture of solidarity and mutual respect. It created a middle class lifestyle for a lot of people,” said Wilson.

Dennis Nobriga, lead mechanic at KT&S, said something similar. “The people against cane burning claimed

—continued on page 4

Crowds surround the tournahauler as it pulls the last batch of sugar cane to the conveyor belt at the Puunene mill.