The bargain: Shipping companies have been able to implement some of the latest technology, the docks are part of one of the nation’s most productive industries, and workers have kept a voice on the job through their union.

Since 1961, as part of the “Mechanization and Modernization Agreement,” dockworkers agreed to new technology as long as they got to share in the savings through wages and pensions. Under that agreement, the employer could put in any new technology or method of work, as long as it was safe and a fair workload. New jobs would be covered by the union contract.

From 1968-2001, productivity grew dramatically, and the workforce shrunk:

• Annual tonnage grew 465 percent in this period;

• In 1968, 13,279 registered longshore workers averaged 1,900 hours and moved 54.5 million tons;

• In 2001, 7,669 longshore workers averaged 2,066 hours and moved 253.4 million tons;

• Productivity growth on the ports averaged 6.6 percent per year, while manufacturing grew at an average of 3 percent from 1968- 2001.

The shipping company APL and the union have worked very closely on a cooperative arrangement on technology over the years. APL has become the industry leader using technology to increase operating efficiency and speed workflow for bigger profit and superior customer service. APL productivity has shot up. The ILWU stands ready to replicate this partnership with other PMA companies.

Safety and health concerns on west coast docks

The Maritime Industry/ Longshore is a dangerous industry with high injury and fatality rates. In 2000, the job injury rate for industries involved with water transportation services was 42 percent higher than the national average.

There have been major safety and health problems on the West Coast docks. This year to date, five ILWU members have been killed on the job in California, crushed by equipment and falling loads or run over by forklifts and vehicles (see attached). In addition, 2 non-ILWU members have also died at California ports this year. According to Cal-OSHA this compares to an average of one fatality a year on the docks over the past decade.

There have also been significant injuries on the docks this year. According to injury records maintained by the PMA, during the period from January 1 – September 6, 2002, there were:

·1126 total injuries in California, 486 (43 %) resulting in lost time.

·353 total injuries in Washington, 151 (43%) resulting in lost time. ·189 total injuries in Oregon, 59 (29%) resulting in lost time.

Major hazards on the docks include moving vehicles and cargo, working under suspended loads, cranes and other overhead equipment, fall hazards/lack of fall protection and inadequate training. In recent years the volume of cargo passing through the ports has increased dramatically, and there has been an increased push for production.

The 13 day lock-out has made the situation even more dangerous. There is cargo piled up on the docks making it more difficult to move equipment and cargo. This is a backlog of ships to be unloaded creating extremely congested conditions. There is a lack of qualified and certified workers to operate cranes, forklift trucks and other equipment. And there is pressure from the court to get the work done quickly, creating even greater hazards.

Provisions need to be made to make sure that safety regulations and the safety provisions of the contract can be followed and are followed, to protect workers from injury or death.

The ILWU and the AFL-CIO have requested U.S. Secretary of Labor Elaine Chao and the governors of California, Oregon and Washington to place federal and state OSHA inspectors on the docks to monitor conditions and to ensure that safety regulations are followed and enforced. (Federal OSHA and the states have shared jurisdiction over safety on the waterfront). State safety agencies have responded and assigned inspectors. But to date the Bush Administration has declined to send federal inspectors to monitor conditions for which it has jurisdiction.

ILWU workplace deaths in 2002

Work in the longshoring and marine terminal industry involves the movement and handling of huge volumes of materials, cargo and passengers to and from ships, barges and other vessels by loading or unloading the cargo to and from the docks, piers, and terminals. The materials and cargo are ultimately moved into and out of the ports via trucks and rail operations.

Work in the harbor is a busy and dangerous. Massive amounts of cargo, often weighing many tons, must be moved during the activities on the docks. Various pieces of equipment are used to move these materials, including cranes, derricks, forklifts and other powered vehicles. The work is frequently performed in situations involving severe space limitations with narrow passageways, limited clearance, and congestion.

Many hazards are present in longshoring and marine terminals that can injure or kill workers. Some of the most frequently occurring safety and health problems in this industry include being struck and run over by vehicles like frontend loaders and forklifts, working under suspended loads, slips, trips, and falls, drowning, and being struck by unbalanced loads and improperly secured cargo.

In 2002, five ILWU members have been killed on the job, all within a six month period:

• On March 14, John Prohoroff of ILWU Local 94 was crushed to death in Long Beach, CA when the line of one of the ship’s cranes broke, dropping a 3,000 pound metal ring 30 feet and hitting Prohoroff.

• On March 15, Mario Gonzalez of ILWU Local 26 died at the Port of Los Angeles while operating a mill that shreds cars into scrap metal. When the mill jammed, Gonzalez entered the mill to fix it but a hydraulic-powered door closed on him, crushing his chest.

• On June 1, ILWU Local 14 member Dick Peters died in the Port of Eureka, CA while checking the hatches of a ship that was being loaded. A crane swung and crushed Peters against the ship.

• On July 23, Richie Lopez, Jr. of ILWU Local 46 died in Port Hueneme, CA after being run over by a heavy forklift truck.

• On September 3, ILWU Local 26 member Rudy Acosta was run over and killed by a top handler in Long Beach, CA.

I LWU labor institutes create an exciting, learning experi ence that is nothing like ordinary school where you can sit quietly in the back of the classroom and take notes. The instructors use a variety of teaching methods that require a lot of active participation from everyone. Participants learned from small group discussions, problem solving, role playing exercises, and the actual work of producing fact sheets, writing leaflets, and organizing rallies.

Institute participants had a fairly demanding schedule of 40 hours of classes over five days. They had a choice of attending 8 out of a total of 25 workshops, which ran from 8:30 AM to 4:30 PM with an hour break for lunch. There were also three night sessions that ran from 6:30 - 8:00 PM which was a stretch of almost 12 hours for three days.

The participants worked hard, learned a lot, and had fun in the process. This is what some of them had to say about their workshops:

“Not boring, gets you going with the excitement of wanting to learn.” —Kathy Kaikuana.

“Very useful class. Practice not just theory.”—Tanya Fujitani.

“Everybody put in their input— great class participation”—Ven Garduque.

“Class was fun and the instructor had a lot of information.”—Ronnie Peralta.

“Subject interesting but classroom time too short.”—Milton Ohira.

Outstanding instructors

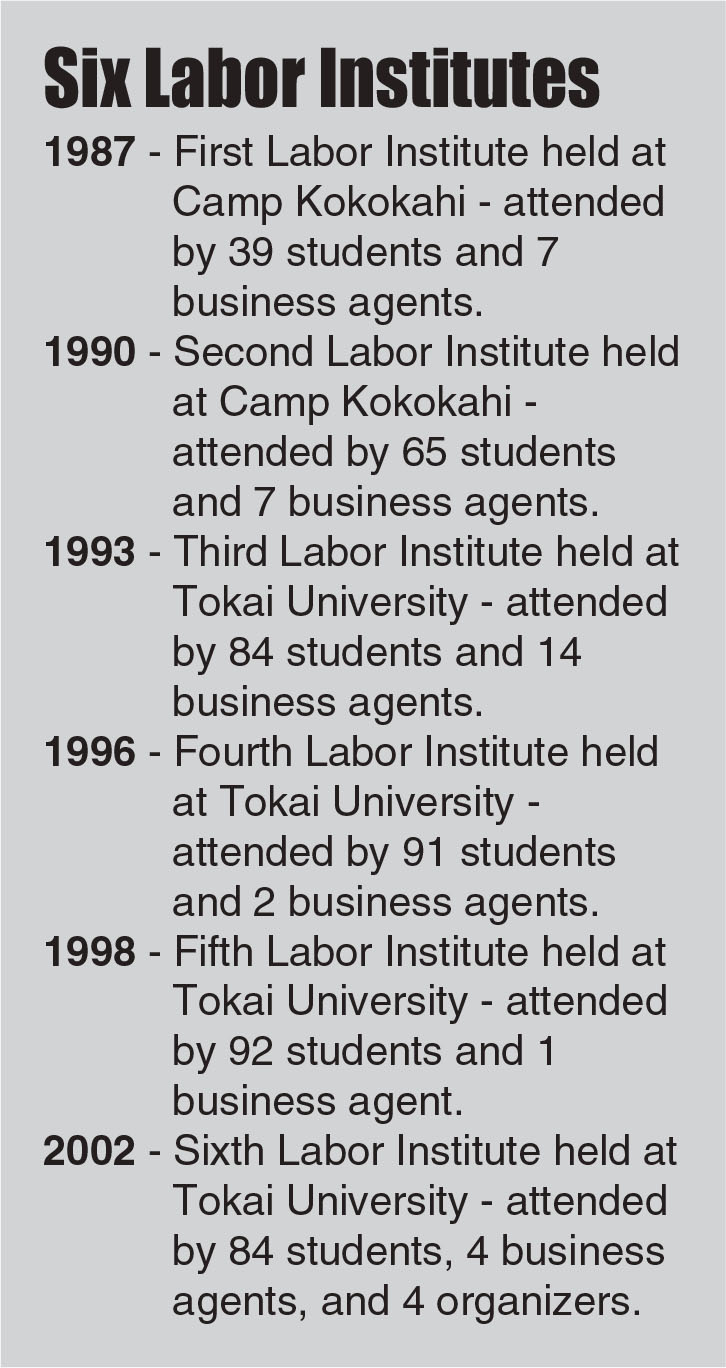

Due to an ever increasing demand for more education, the labor institute has grown to allow the attendance of over 100 people. This is more than double the number of members who attended the first labor institute in 1987, which could only accommodate 46 people.

A teaching staff of at least 11 are required to teach an institute of this size, and only four labor educators are available at the University of Hawaii’s Center for Labor Education and Research. In addition, labor educators are not ordinary teachers, as it requires specialized skills and teaching methods to effectively teach adult workers.

The ILWU found a novel solution to this problem by offering mainland labor educators a free trip to Hawaii in exchange for teaching. Over the years, this has worked extremely well. There has never been a shortage of volunteers from the mainland and all of the instructors have done an outstanding job. It also gives Hawaii an opportunity to learn from the experience of the labor movement on the Mainland.

Over the years, the content of the training has also changed in response to new challenges facing the union movement. The goal of this year’s institute was to arm unit leaders with the skills and knowledge to lead and involve members in contract campaigns at their worksites. The idea behind contract campaigns (also called “strategic” or “coordinated” campaigns) is not new. Contract campaigns simply bring together many different tactics unions have long been using to improve the conditions of working people.

In a typical contract campaign members are organized, mobilized, and involved from the very beginning. Second, the union develops a strategic plan based on research and gathering as much information as possible on the vulnerabilities of the employer. Third, the union broadens the struggle to gain community support and to target all parts of the employer’s business and economic relationships. Fourth, union members are prepared to use a wide variety of pressure tactics, which are coordinated to gradually increase pressure and encourage management to settle a fair contract.

Stronger unity and commitment

Educational programs like the labor institute do more than teach skills and enhance knowledge— they also build solidarity and refresh the spirit. On the job, union activists can sometimes feel isolated and lonely, like they’re the only ones who care and are committed to building the union. At the institute, however, they are among a hundred other ILWU members who think and feel exactly like them. They spend a week together—searching for answers, sharing experiences, and learning from each other—and the process restores their energy and renews their enthusiasm as union activists.

At graduation, which was held at the end of the institute on Friday night, the energy and enthusiasm of the participants had reached a high point. “You are all charged up,” observed Vice President Robert Girald in his remarks. “There’s a lot of fire in you. Go back to your units and try to fire up your fellow members. Share your knowledge.”

“Education will become more and more important in this union,” Girald said. “We’re dealing with a different type of employer and a changing economy and this requires us to do a lot of reading and research. The only way the union can prepare you is for us to provide you with more and more education.”

Moving experience

The unique experience of the ILWU labor institute also touches the instructors. Dawn Addy, who taught at two earlier institutes, explained that the Aloha spirit of ILWU members keeps her coming back. She was also impressed by the “amazing energy of the new people.” Unlike earlier institutes where a majority of the participants are veteran unionists, this institute had a majority of new leaders.

First time instructor Grainger Ledbetter was particularly touched by the enthusiasm for education and knowledge he found among ILWU members. “Rarely if ever has my teaching been so appreciated,” he said, as he explained how the people in his workshop demanded copies of overhead transparencies.

Amelia Stalker, Linda Fernandez, Shawn Atacador, and Willie Stalker of Unit 2509 - Lanai Company, Inc. “We no longer feel isolated.”