The Report of the Officers is a unique and important part of ILWU democracy. It reaffirms that the rank and file at this Convention make the policies that guide the work of this union. It reaffirms that the Titled Officers must take their direction from the membership.

In this report, the Local President, Vice President, and Secretary-Treasurer review the major work, accomplishments, and shortcomings of our Union during the last three years.

Farm Bill brings stability to Sugar industry

Amfac Sugar Kauai brought in their last harvest in November 2000, and the remaining workforce of 200 were permanently laidoff. The closure leaves only two sugar companies left in Hawaii—HC&S on Maui and Gay & Robinson on Kauai.

In the last 10 years, nine sugar companies went out of business, putting 2,200 ILWU members out of work and destroying the economic livelihood of many rural communities in Hawaii. These workers and their communities were victims of one-sided US trade policies, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), that are mainly designed to protect and maximize profits for US companies while doing nothing for working people and consumers.

The Bush Administration is pushing for the passage of another trade agreement, the Free Trade Area of the Americas, which would extend NAFTA-like trade agreements to the countries of South and Central America. This agreement is scheduled to be implemented at the end of 2004 and would probably mean the end of Hawaii’s sugar and pineapple industries.

There was some good news for our sugar members. The 2002 U.S. Farm Bill keeps most of the sugar program in place, including sugar price supports of 18 cents a pound for cane sugar. Every several years the Farm Bill comes up for renewal and the big industrial users of sugar, like Campbell Soup and Coca Cola, constantly try to reduce the 18 cents or cut sugar out of the program so they can get their hands on cheaper foreign sugar. Any reduction in the 18 cents price support would destroy

the sugar industry in Hawaii and in most of the United States.

In an uncanny coincidence, a delegation of members from our sugar units were in Washington, D.C. on September 11, 2001, to lobby Congress to keep the sugar program in the Farm Bill.

The 2002 Farm Bill provides some stability to the industry, which enabled our members at HC&S on Maui to win a five-year contract with an unprecedented 3 percent wage increase each year. The contract with Gay & Robinson on Kauai expires this year. ◆

Longshore gain control over technology

West Coast longshore negotiations dominated the attention of our union and our longshore members from June 2002 to January 2003. Even before negotiations started, the association of longshore employers, the PMA, made it clear they were

going to take on the ILWU. The PMA began to line up their supporters in the Bush Administration and among big corporations like K-Mart. Negotiations centered around very difficult issues of technology and jurisdiction.

Talks got nowhere in the adversarial conditions created by the PMA. On September 27, 2002, the PMA locked out the union. On October 9, citing national security concerns, President Bush ordered the ports reopened and the union and management to return to the bargaining table. After the lockout, the backlog of cargo, congestion, and chaos severely affected the normal

flow of cargo on the docks. The PMA tried to blame the union for the drop in productivity.

The attempt to shift the blame backfired on the PMA. On November 14, at a hearing before a U.S. District judge, the Justice Department agreed with the union that the PMA was to blame for the chaos and loss of productivity.

The PMA finally settled down to serious bargaining, and a tentative agreement was reached 9 days later on November 23, The agreement was approved by the full longshore caucus on December 12, 2002, and ratified by the members by January 23, 2003.

Following the successful completion of the West Coast longshore agreement, similar agreements were hammered out for our Hawaii longshore members. Substantial improvements were made in pension benefits, but this required a trade off with wage increases coming at the end of the 6-year agreement. Wage increases for longshore were about 2% in 2000 and 2001 and 0%

in 2002 and 2003.

Strategic Victory

The 2002 longshore agreement was a major, strategic victory for the ILWU by giving the union a say in new computer technology that threatened to eliminate the jobs of hundreds of ILWU marine clerks.

A special agreement on the application of technologies and preservation of marine clerk jurisdiction was worked out .Management is required to discuss new operations and technology with the union, provide information needed to understand issues, and bargain over the issues.

All work created or modified by technology within the traditional jurisdiction of marine clerk work stays with the clerks. All current jobs are protected and major increases were made in pension benefits to encourage clerks to retire.

In most American workplaces, management has total control over the introduction of new technology. Where this is the case, management will always use new technology to increase productivity, so that a few workers can do the work of many. This allows management to cut jobs and maximize their profits. Management gets all the benefit of technology, while workers are the victims.

The ILWU longshore division, however, has had a say in new technology ever since the Mechanization and Modernization Agreement of 1961. Under the leadership of ILWU president Harry Bridges, a breakthrough was made in the way the union approached the issue of new technology. Basically, Bridges understood that workers could never win in the long run by standing in the way of modernization.

The only winning strategy was to cooperate with management in making the workplace more efficient, but to make sure that the union had a say in how technology is implemented and that workers shared in the benefit. ◆

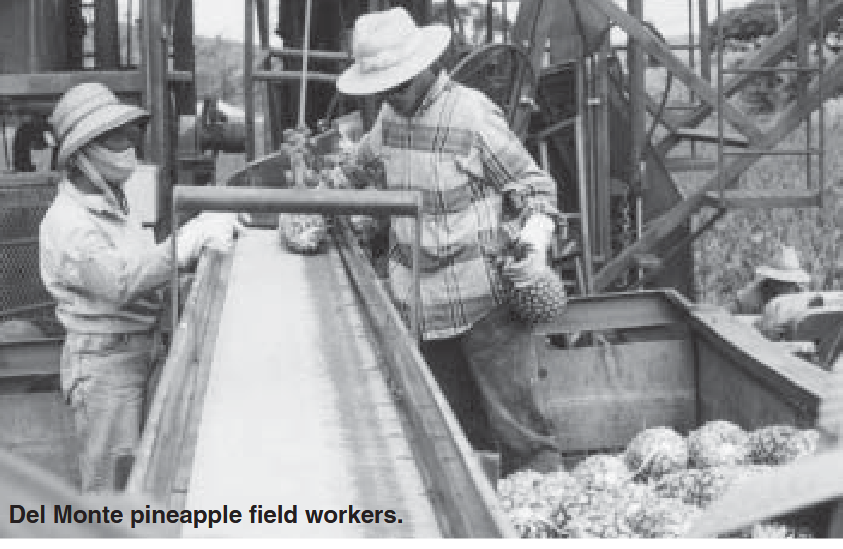

Pineapple struggles against global giants

There are three companies in our pineapple grouping that are facing very different financial situations. Dole and Del Monte have been making money, while Maui Land and Pineapple has lost money in the last two years.

Maui Land and Pineapple is a Hawaii-based company in three lines of business—pineapple, tourism, and commercial property. The company employs about 2,000 people and generates about $100 million in revenues from pineapple and $50

million from their resort and commercial property. The company produces fresh pineapple and operates the only pineapple cannery left in the U.S. Growing losses from their canned pineapple operations had led the company to focus more on fresh

—continued on next page

ILWU Local 142 Officers Report on the Work of the Union

Pineapple, (continued)

pineapple. The company reported a loss of $4 million in the first 6- months of 2003 and $5.6 million in 2002. The company made a profit of $7.5 million in 2001.

Dole and Del Monte are classic examples of how companies have globalized production to take advantage of lower labor costs in the developing countries. Both companies no longer produce canned pineapple in Hawaii. Instead, they focus on the more profitable fresh and fresh-cut pineapple. Canned pineapple sold under the Dole and Del Monte brands come from Thai-

land or the Philippines.

Del Monte’s global operation

Del Monte is a global, multi-national company that operates in 50 countries, has 25,000 employees, and does business in a large variety of fruits and vegetables. The company does over $2 billion in business and has been reporting record profits in

the last few years. Bananas account for most of the company’s sales, but fresh and fresh-cut pineapple is Del Monte’s biggest and most important profit maker. The company reported a record high net income of $195 million in 2002. The company produces pineapple in Costa Rica, the Philippines, and Hawaii and has 50% of the pineapple market in the United States.

Multi-national giant Dole Foods

Dole Foods is an even bigger global company that employs 57,000 people in 90 countries with $4.4 billion in annual revenues. In the last two years, pineapple and fresh fruits have been the companies best and most important line of business,

accounting for about two-thirds of the company’s revenues and income. Income from fresh fruits and pineapples have increased astronomically from $1.5 million in 2000 to $217.8 million in 2002. The company grows pineapples in Latin America, Hawaii, Philippines and Thailand. Dole reported a 2002 income of $156 million, but took an accounting loss

of $120 million.

Due to the turbulent situation with West Coast longshore bargaining at the time, the union negotiating committees from Dole, Del Monte, and Maui Land and Pineapple, decided to extend the contract which was to expire on November 30, 2002,

for one year until January 31, 2003. In January 2003, the union committees agreed to a second one-year extension because of the impending war with Iraq and to give Maui Land and Pineapple time to improve its financial situation. ◆

9/11, SARS, and Iraq War hurt our Tourism Grouping

There are 11,000 members in our Tourism Grouping, which is more than half the membership of Local 142. This grouping includes hotels, golf courses, and industries related to tourism.

Favored Nations Battle Won

Our union won a significant victory with a contract settlement at the Royal Lahaina Hotel in March 2001 which finally limited the hotel’s use of the “favored nations clause.” The “favored nations clause” was part of a legal and contractual dispute between the union and a number of hotels which goes back to 1994.

In 1994, almost all of the neighbor island hotels organized by the ILWU were members of the Council of Hawaii Hotels and covered under a master hotel contract with the same wages, benefits, and contract language. The industry was going through rough economic times and the Council asked the union for help.

ILWU hotel members agreed to make a sacrifice and help the hotels by postponing a number of wage increases, with the understanding the hotels would restore all negotiated increases on the last day of the contract.

ILWU members protest Pacific Beach Hotel’s violation of worker rights.

The hotels were also concerned about competition from new hotels like the Grand Wailea that were not members of the Council of Hawaii Hotels. They did not want these non-Council hotels to have an advantage if the ILWU negotiated a cheaper

contract with that hotel. To prevent this, the Council wanted a “favored nations clause” which would allow them to implement any cheaper terms from these other contracts. The union agreed, with the understanding that “favored nations” was temporary and would drop dead when the contract expired in May 1995.

When the contract expired in 1995— the hotels, under the influence of management attorney Robert Katz, quit the Council and began negotiating separate contracts with the union. The hotels also betrayed their employees and refused to honor their agreement to restore the last wage increase. Some hotels, like the Royal Lahaina and the Renaissance Wailea Resort, took the

position they had the right to continue using the favored nations clause, even though the contract had expired and they were no longer part of the Council.

The Maui hotels, advised by Robert Katz, and the Big Island hotels, advised by management attorney Ron Leong, told the union they would stop deducting dues unless the union agreed to extend the contract without the last wage increase. The union could not agree to give up a wage increase promised to our members; the hotels stopped deducting union dues; and ILWU hotel members began an industry-wide struggle for fair contracts that would take several years to resolve.

To make a long story shorter, the union won fair contracts at most hotels, supported in part by National Labor Relations Board decisions and arbitration awards in the union’s favor. Favored nations remained an issue at the Royal Lahaina which was finally resolved by the March 2001 agreement.

Mobilizing Project

The success at the Royal Lahaina was only possible because the Local committed massive additional resources in the form of the Tourism Mobilizing Project.

The Mobilizing Project was conceived in mid-1999 as a way to rebuild and focus union and member power in the hotel industry for the year 2000 negotiations. Industry bargaining had broken up after the 1995 contract, separate and diverging agreements were negotiated at each hotel, and the favored nations clause in some contracts was a major threat to union standards.

The idea of the Mobilizing Project was to maximize the union’s bargaining power in contract negotiations by mobilizing

members and waging a corporate campaign against that employer. The Project would research an employer’s weaknesses and vulnerable points, then organize to put pressure on that employer through member mobilizing, taking the struggle to the community, reaching customers or clients or shareholders, using government agencies and regulations, and other tactics.

The Project started in early 2000 and worked with the Hyatt Maui, the Grand Wailea Resort, and the Royal Lahaina hotels. The Project had a temporary staff of 5 full-time people—a director, a researcher, and three mobilizers. The Project ended

in mid-2001 and the final report and training session for our full-time officers was held on August 14, 2002 as part of the ILWU Labor Institute.

The Project was successful—good contracts were won at the Hyatt Maui, Grand Wailea, and Royal Lahaina; the success of the Project’s contract campaigns created a stronger climate of mobilizing within our organization; and the lessons learned

from the Project were passed on to our full-time officers and many unit leaders.

9/11 Shock

Our tourism members were hit by the severe shock to the tourism industry following September 11, 2001. The disruption to air travel, the focus on airport security, the Bush Administration’s decision to fight a global war against terrorism and to start that war by overthrowing the Taliban government of Afghanistan created a climate of fear and uncertainty which caused a 25% decline in visitors to Hawaii. This included a 50% drop in Japanese visitors.

For the next six months, hotels cut hours and laid off hundreds of workers. Our union was kept busy making sure the hotels followed seniority and other contract terms as they cut hours and laid off workers. We also sought extended unemployment insurance and medical coverage to help members who lost their jobs. Several food bank distributions were made.

The loss of income suffered by our hotel members also caused a serious drop in our union’s dues revenues, which are based on a percentage of income.

This required the officers to take a series of steps to safeguard the financial health of our union. An FTO wage increase scheduled for January 2002 was suspended, new programs were put on hold, and all expenses that could be delayed were

put off. In practice this applied mostly to the purchase of equipment and educational classes, which were expenses completely under our control.

Visitor arrivals gradually recovered towards the middle of 2002, which enabled us to gradually restore all programs and to give the FTOs a wage increase as of October 2002.

Iraq War Shock

The hotel industry took another hit in late 2002, when President Bush began the buildup for a war against Iraq and asked Congress for authority to use military force against Iraq. Waikiki and the Big Island suffered the greatest loss, while Maui and

Kauai were not seriously affected. When Bush finally launched the

—continued on page 7