—continued from page 3

in the door, its presence spread rapidly. Within weeks, it had taken over the financial functions of Basra’s civil administration. Workers, in order to get paid, had to take their time sheets to local KBR offices for approval. Those who had fled the advancing troops had to get company permission to return to their jobs.

Then KBR claimed the work of reconstructing wells, pipelines and other oil facilities, and hired a Kuwaiti contractor, Al Khoorafi, to bring in a foreign workforce. Meanwhile, the company used its presence in the oil fields to try to hire drilling rig workers away from the Iraqi Drilling Company, a national enterprise. Despite promises of higher wages, few took the bait. Nevertheless, Iraqi oil workers were outraged. With unemployment hovering at 70 percent, they saw a clear threat to their jobs. But according to Juma’a Awad, workers had other concerns as well.

“We organized the union for two reasons,” he said. “First, we had to deal with the administration put in place by the occupying forces. Second, we’re afraid that the purpose of the occupation is to take control of the oil industry. It is our duty as Iraqi workers to protect the oil installations, since they are the property of the Iraqi people. We’re sure that U.S. and international companies are here to put their hands on the oil.”

Organizing oil and power plants

By August 2003, oil workers had organized unions in ten state-owned companies in southern Iraq and formed the General Union of Oil Employees (GUOE). They gave KBR an Aug. 20 deadline to leave the oil sector. When the company refused to talk with them, they shut down oil production for export.

“For two days we didn’t move,” said Farouk Sadiq, a union leader and teacher at Basra’s Oil Institute. “We refused to pump a single drop until they left. We said we wanted them to leave by peaceful means— otherwise we had another language to speak with them. Other workers in Basra refused to work too, and the American authority saw we could affect what really matters to them. It was independence day for oil labor.

KBR did leave the oil districts, and closed their offices in Basra. In December the union challenged Bremer’s wage orders, threatening to strike again if wages were lowered. This time, the oil minister caved in without a work stoppage. Eventually, the bottom two wage grades were abolished in the oil industry, bringing the base wage up to about $85 per month.

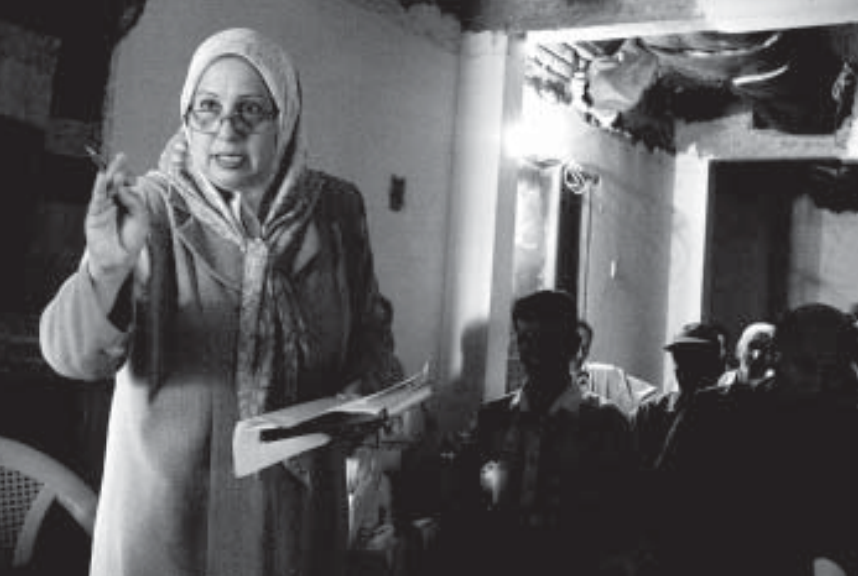

The GUOE then helped workers organize in the power generation plants. Hashimia Mohsen al Hussein was elected president, the first woman to head a national union in Iraq. In January 2004, unrest spread to the Najibeeya, Haartha and Al Zubeir electrical generating stations, where workers mounted a wildcat strike, stormed the administration buildings, declared the September wage schedule void and vowed to shut off power if salaries were not raised. Again the ministry agreed to return to the old scale.

Building an Iraq “free of privatization”

Last June the union organized large demonstrations to protest government decisions to hire private contractors to do reconstruction work, replacing the industry’s own employees. The problem persists.

“We will confront them if they don’t stop,” Mohsen warned. “Many Basra workers have already agreed to join us in a general strike.”

On the ground in southern Iraq, a new labor movement is being born. Some unions, like the oil workers, are independent. Others, like those for power and longshore workers, are affiliated to the Iraqi Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU). They all cooperate in confronting the occupation’s economic policies for keeping wages low, subcontracting jobs and privatizing major industrial enterprises.

In May the GUOE organized a conference at the cultural center of the oil industry in downtown Basra under a banner calling on Iraqis “To revive the public sector and build an Iraq free of privatization.” Bringing together union leaders from rigs and refineries, economists from Basra University, representatives of the IFTU and political parties from the Supreme Council of the Islamic Revolution in Iraq to Iraq’s Communists, the conference sought to forge a consensus to resist oil privatization.

Hashimia Mohsen al Hussein, the president of the Basra engineering union that represents workers at electrical power stations, is the first woman to head a national union in Iraq. Mohsen condemns the management of the power industry for refusing to talk with the union, citing Saddam Hussein’s law banning unions for workers in the public sector. She also condemns the contracting of jobs to foreign companies, especially given Iraq‘s unemployment rate of 50-70 percent.

“The public sector economy of Iraq is one of the symbols of the achievement of Iraqis since the revolution of July 4th, 1958,” the conference statement declared.

According to oil industry analyst Greg Muttitt, who attended the conference representing the British organization Platform, a nongovernmental organization concerned with issues of globalization, it is unlikely that oil reserves themselves would be sold, or that a foreign company or government would be given a concession like the one the British held for over three decades. Outside of the U.S., no other country permits those forms of ownership.

“More likely, Iraq’s debt will be used to force the government to sign production-sharing agreements with the multi-nationals,” Muttitt said.

foreign company to extract the oil, sell it to pay itself for the costs of extraction—by its own calculation— and split the remainder of the income with the government.

Drilling a new well in the South Rumeila field (Iraq’s largest).

Iraq’s government would be locked into long-term, disadvantageous agreements, in which it would lose control over most decisions regarding oil exploitation, pricing, income and jobs. Oil workers would likely suffer massive layoffs and lose their leverage over production. Juma’a Awad stressed that without the oil income, Iraq will be unable to rebuild from the war.

“Oil is the first step in jumpstarting the economy,” he said. “We don’t want to pay the cost of globalization.”

While rank-and-file workers are unfamiliar with the details of production-sharing agreements, they are suspicious of privatization, despite the carrot of modernization used by its defenders to make it attractive. In the Basra refinery, senior fireman Abdul Faisal Jaleel criticizes Saddam Hussein’s long failure to invest in modern technology, or even spare parts, and said workers paid the price.

“We’ve been like the camel that carries gold, but is given thorns to eat.” Nevertheless, he said, foreign ownership is not the answer. “We reject foreign investment. We want to keep our own oil revenues and use them to develop our country with our own hands.”

Unions are suspicious of Iraq’s elite political class, returning from exile and enamored with the ideology of the market economy. But they recognize that the government only nominally holds the power to make these economic decisions, and that the real push to privatize comes from Washington and London. This is just one reason why all Iraqi unions call for an end to the occupation and the cancellation of the country’s foreign debt.

They don’t agree on timing or method. The GUOE calls for immediate withdrawal of foreign troops. The IFTU says an elected Iraqi government should use UN resolution 1545 to ask them to leave. The Federation of Workers’ Councils and Unions of Iraq (FWCUI), Iraq’s other main labor federation (outside of Kurdistan), calls for UN troops to intervene to supply security. But Abood Umara voiced their common perception that the economic plan of the occupation would bring Iraq back to the early 1950s, before oil was nationalized and Iraq was ruled by the British behind the facade of a native monarchy.

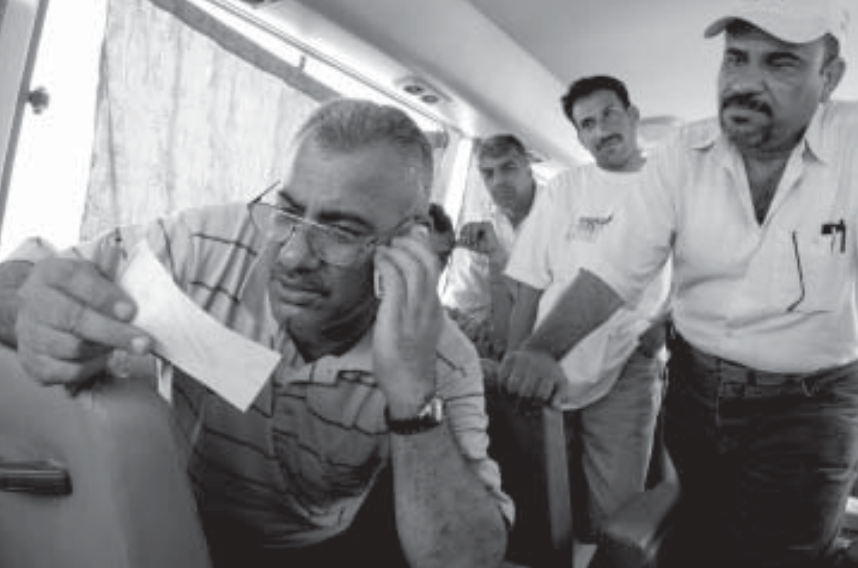

Felah Abood Umara, general secretary of the General Union of Oil Employees (GUOE), with other leaders of the union.

Unions as targets of terror and troops

The occupation, however, is not their only enemy. On Feb. 18, Ali Hassan Abd (Abu, or Uncle, Fahad), a leader of the IFTU-affiliated union at Baghdad’s Al Daura oil refinery, was walking home from with his young children, when gunmen ran up and shot him. Less than a week later, armed men gunned down Ahmed Adris Abbas in Baghdad’s Martyrs’ Square. Adris Abbas was an activist in the Transport and Communications Union, another IFTU affiliate. The murder of the two followed the torture and assassination of Hadi Saleh, the IFTU’s international secretary, in Baghdad Jan. 4.

Abood Umara refers to them all as “our leaders” despite the fact that the GUOE is not part of the IFTU, and condemns terrorism and assassination. He adds that a bomb was found in the car of a GUOE member earlier this year, fortunately before it was detonated, and that Hassan Juma’a Awad has received death threats.

Last fall, armed insurgents attacked freight trains, killing four workers in November, and beating and kidnapping others a month later. Service was suspended between Basra and Baghdad after workers threatened to strike over lack of security.

They say they’re being blamed for helping the occupation by doing their jobs, although the trains don’t carry military goods.

ilitary goods. "It's [a risk for all] civil society organizations, including trade unions,” Saleh explained at a meeting of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions in Japan in December, just before his murder. “Extremists who target trade unionists, both teachers and engineers, kill them under the notion that they are collaborating with a state created by the Americans, so by definition those are collaborators and legitimate targets.”

Attacks come from the government and U.S. occupation troops as well. Baghdad’s Transport and Communication workers were thrown out of their office in the city’s central bus station in December 2003 by U.S. soldiers, who then arrested members of the IFTU executive board. Qasim Hadi, general secretary of the Union of the Unemployed (part of the FWCUI), was arrested several times by occupation troops, for leading demonstrations of unemployed workers demanding unemployment benefits and jobs. Last fall, when textile workers in Kut struck over pay, the city governor called out the Iraqi National Guard, which fired on them, wounding four.

In the broader context of anti-union violence, IFTU leaders are probably singled out as a response to the union’s position on the January elections, another issue on which Iraqi unions disagree.

“The IFTU supports democratic principles,” explained Ghasib Hassan, head of the IFTU’s Railway and Aviation Union. “And one of those principles is elections. So we supported them.”

The IFTU, like other Iraqi labor federations, has close relations with a set of political parties, in its case the Iraqi Communist Party (with two ministers in the current government),

—continued on page 6