BASRA, IRAQ (6/29/05)—Originally organized under the British in the early 1920s, the Iraqi oil union has always been the heart of the country’s labor movement.

“Iraq’s two biggest strikes, in 1946 and 1952, were organized by oil workers,” Faleh Abood Umara, general secretary of the newly reorganized General Union of Oil Employees, told officers and members of the ILWU during a visit to the West Coast by himself and Hassan Juma’a Awad, the union’s president.

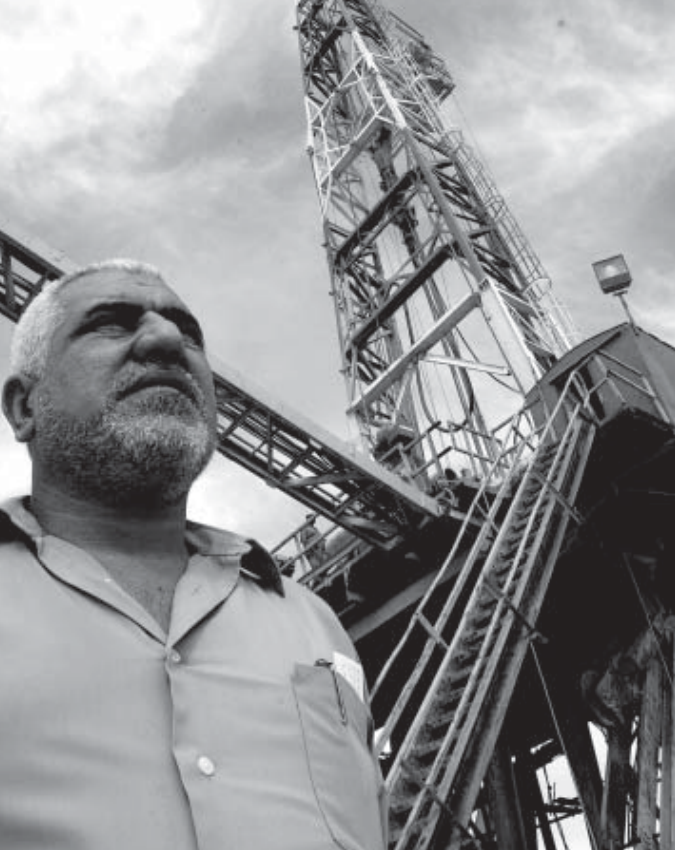

Hassan Juma’a Awad, the head of the General Union of Oil Employees, the largest and most powerful union in Iraq, was organized after the fall of Saddam Hussein.

Today it is again Iraq’s largest, most powerful labor organization, with 23,000 members in southern Iraq. Together with two other labor federations and a handful of independent professional associations, the labor movement is now the biggest institution in Iraqi civil society.

From the very first day of the occupation, Iraqi labor has had to operate in illegal conditions, which has produced a militant and fighting movement, especially in oil. That spirit was evident on the morning of April 9, 2003, the day the US/British invasion started. Workers at Basra’s huge, dilapidated oil refinery knew it might come at any moment. Nevertheless, no one expected American tanks when they suddenly pulled up at the gate.

After 30 years of Saddam Hussein, the vast majority had had their fill of war and repression. They were prepared to welcome almost any change that removed the old regime, even foreign troops.

“We were coming out early, at the end of our shift, and there was the American army,” recalled Faraj Arbat, one of the plant’s firemen. “We were ready to say, “Hello.”

Instead of greeting the workers and acting like their liberators, however, the soldiers trained guns on them. The head of the fire department made the mistake of questioning the troops, and was ordered to lie facedown on the ground.

“Abdulritha was absolutely shocked,” Arbat recalled. “He was going home. Why should he lie down? But he did as he was ordered. Then an American put his foot on his back. So we started fighting with the soldiers with our fists, because we didn’t understand. The tank turret started to turn toward us, and at that point we all sat down.”

Someone easily could have died that day. As it was, the memory of the foot on Abdulritha’s back left a bitter taste.

The refinery’s workers had already labored through the shelling and fires of two decades of conflict, including the “shock and awe” bombing prior to the invasion. Some fled the arriving troops, but most stayed and tried to bring the plant back into operation.

“Slowly we got production restored, by our own efforts,” Arbat said. “Electricity workers, at their own expense, brought power back to the refinery. We found where the water pipes had been blown up and went out with armed guards to repair them. Meanwhile, the Americans and British began coming with tanker trucks, loading up on the gas and oil we were producing.”

For two months, no one got paid. Finally, Arbat and a small group began to organize a union.

“At first the word frightened people, because under Saddam unions had become instruments of oppression,” he explained.

Nevertheless, a few dozen of the refinery’s 3,000 employees came together and chose Arbat (whom they affectionately call Abu, or Uncle, Rebab) and Ibrahim Radiy to lead them.

To force authorities to pay the workers, the small group took a crane out to the gate and lowered it across the road. Behind it, two dozen tanker trucks pulled up with a heavily armed military escort.

“At first there were only 100 of us, but workers began coming out,” Arbat said. “Some took their shirts off and told the troops, ‘Shoot us.’ Others lay down on the ground.”

Ten of them even went under the tankers, brandishing cigarette lighters. They announced that if the soldiers fired, they would set the tankers alight.

The soldiers, mostly sons of workers themselves, did not fire. Instead, negotiations began between the general director and the occupation authorities in Basra. By the end of the day the workers had their pay. Within a week, everyone at the refinery joined, and the oil union in Basra was reborn.

Organizing for jobs and against privatization

Like other unions in Iraq’s stateowned enterprises, the oil union has had to function as an illegal organization. That hasn’t kept unions from organizing to successfully challenge the occupation, however. In fact, the first big fight over the U.S. and British economic program came within a few months of the confrontation at the Basra refinery gate. KBR, a subsidiary of the oil services giant Halliburton, was one of the corporate camp followers arriving in the wake of the troops. KBR was given a no-bid contract to put out war-caused oil fires in the huge Rumeila fields, but once its foot was

—continued on page 4