The Constitution of the United States

Article I. Section 8. The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and

provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform

throughout the United States;

To declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water; To raise and support armies, but no appropriation of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years; To provide and maintain a navy; To make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces; To provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the union, suppress insurrections and repel invasions; To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining the militia, and for governing such part of them as may be employed in the service of the United States, reserving to the states respectively, the appointment of the officers, and the authority of training the militia according to the discipline prescribed by

Congress;

Article II. Section 2. The President shall be commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several states, when called into the actual service of the United States . . .

The President has the power to repel attacks

The Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power “to declare war.” An earlier draft had the wording “to make war.” This was changed with the understanding that “make” war was understood to “conduct” war which was more a function of the Executive branch or presidency. in other words, Congress makes policy, the President carries out the policy.

The Constitution was the work of representatives from the 13 former colonies who met for five months in 1787 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Notes on the debates and discussion of the delegates can be found at: www.constitution.org/dfc/

dfc_0000.htm.

President can repel,not commence attacks

On August 17, 1787:Mr. James MADISON and Mr. Elbridge GERRY moved to insert “declare,” striking out “make” war; leaving to the Executive the power to repel sudden attacks. Mr. Roger SHERMAN thought it stood very well. The Executive

should be able to repel, and not to commence, war. “Make” is better than declare, the latter narrowing the power too much.

Mr. GERRY never expected to hear, in a republic, a motion to empower the Executive alone to declare war.

Mr. Oliver ELLSWORTH: There is a material difference between the cases of making war and making peace. It should be

more easy to get out of war, than in to it. War also is a simple and overt declaration, peace attended with intricate and secret negotiations.

Mr. George MASON was against giving the power of war to the Executive, because not safely to be trusted with it; or to the

Senate, because not so constructed as to be entitled to it. He was for clogging, rather than facilitating war; but for facilitating peace.

On the remark by Mr. King that “make” war might be understood to “conduct” it which was an Executive function, Mr. Ellsworth gave up his objection, and the vote of Connecticut was changed to-ay. Passed by a vote of 8 to 1.

Peace treaties authorized by Senate

September 7, 1787: Mr. MADISON then moved to authorize a concurrence of two-thirds of the Senate to make treaties of peace, without the concurrence of the President. The President, he said, would necessarily derive so much power and importance from a state of War, that he might be tempted, if authorized, to impede a treaty of peace.

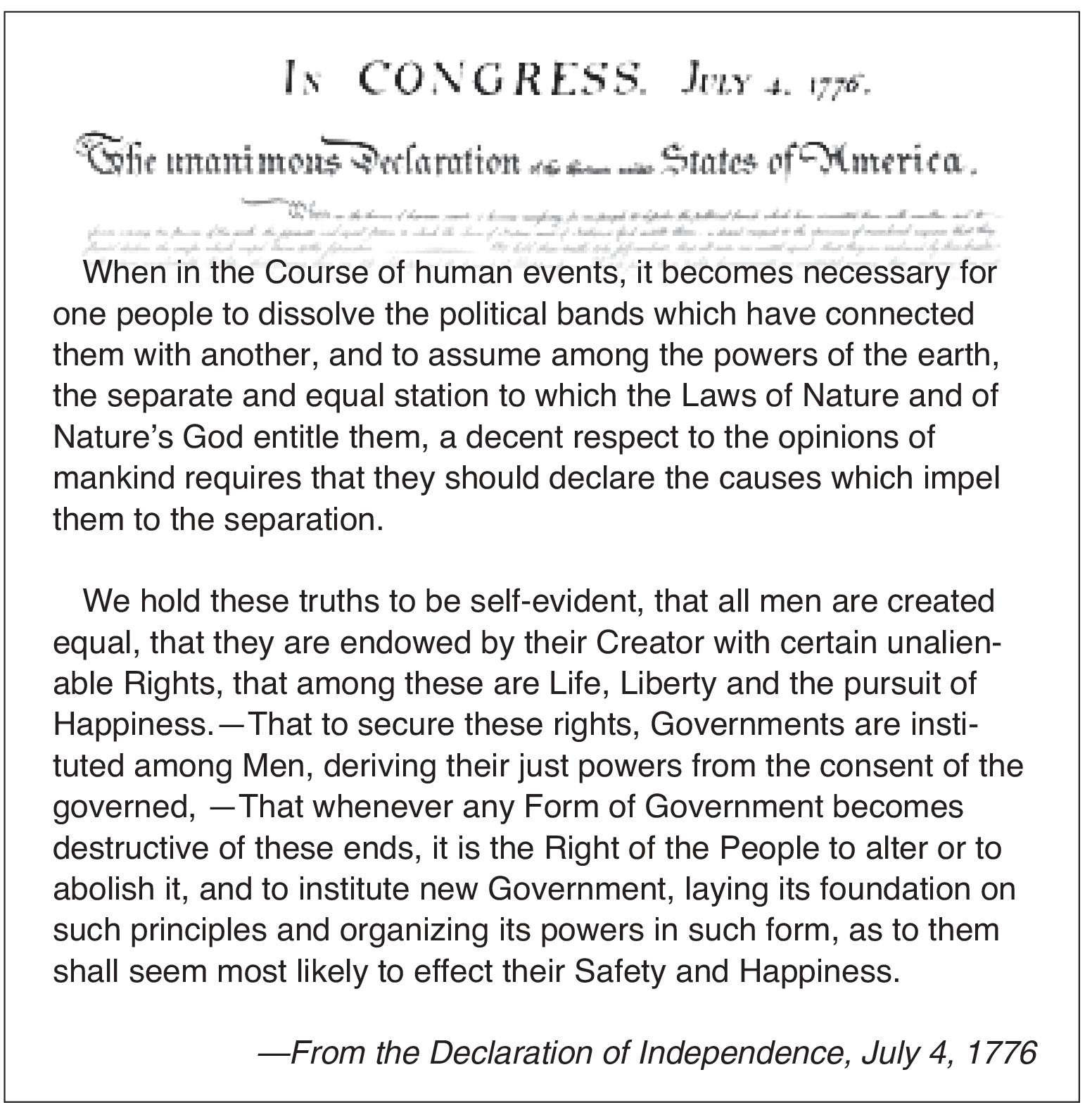

U.S. Declaration of Independence

The U.S. Declaration of Independence reminds us that the people must stand above the government—that government derives its power from the people, and the people have the right to change their government.