In the United States, an employee who does not have a union or any kind of agreement with their employer over job security, is considered an “at will” employee. This pretty much means all nonunion workers in private industry—or about 70 percent of U.S. workers—are at will.

An “at will” worker may be terminated by their employer at any time and for any or no reason. This means that a boss could wake up one morning and decide to fire the first employee he sees that day. As unfair as this may seem, it is perfectly legal under U.S. law.

The origin of this law goes back to the late 1800s, a time when a handful of American capitalists amassed immense wealth and political power through their control of railroads, and later mass production factories and the banking system. The “at will” doctrine fit perfectly with their need for a disposal and unskilled workforce in their steel mills and giant factories.

The idea of “at will” first appeared in 1877 in a legal treatise by Horace C. Wood, when he wrote in Master and Servant that—“a general or indefinite hiring is prima facie a hiring at will” and can be ended at will by either party without liability. This broke from the English common-law rule that a general hiring was for a term of one year.

American judges picked up on this concept and within a few years, the “at will” doctrine included the idea that

employers could dismiss employees for any reason. In 1884, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Western & Atlantic Railroad Company that: “All may dismiss their employees at will, be they many or few, for good cause, for no cause or even for cause morally wrong, without being thereby guilty of legal wrong.”

The railroad had issued an order that any employee who shopped at particular store would be discharged. The store owner, a man named Mr. Payne, sued the railroad, but the court upheld that the railroad had the “right” to fire at will.

Limits on At Will

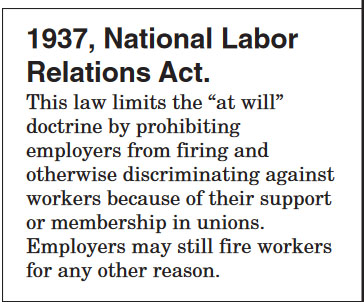

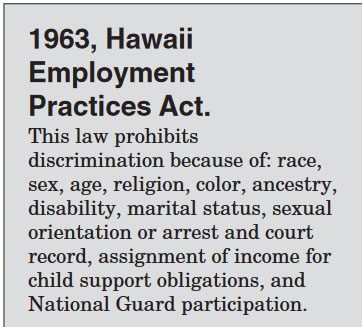

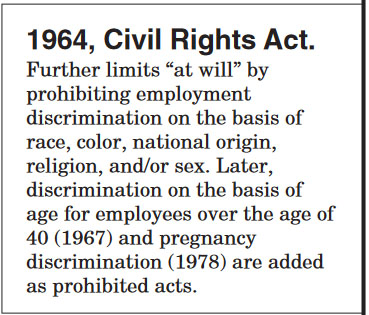

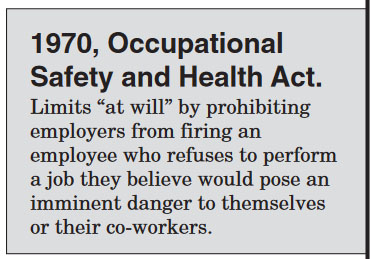

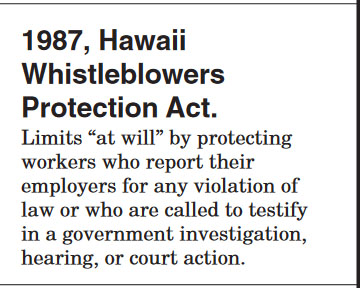

This idea of “at will” employment remains the law in nearly every state today. However, mostly through the success of union political action, a number of laws have been passed that protect employees and place important limits on an employer’s “freedom” to fire employees at will. Six of these laws are described at right.

These are six more examples of how union political action has improved the lives of working people. You can do your part by registering to vote and supporting the candidates endorsed by the ILWU Political Action Committee. The union endorses candidates who support programs that benefit working families.

See page 4 for a diagram of the structure of the ILWU